As the end-of-year lists start coming out, the sameness of them is sometimes a little bit depressing, even if I like the films showing up on every list. (It’s even more depressing when I don’t like them). Then there are the weird times when a film I truly and wholeheartedly dislike shows up on every list. There’s always one of those movies a year! I feel no pressure to submit to consensus but still, it’s weird when everyone around you is screaming about some masterpiece you find annoying, reductive, or just plain old stupid. My point is: Diversity, variety, and lack of consensus is healthy and a good sign for film culture. I am all for lack of consensus.

I wanted to share a list of films I loved this year. Some of these films are on my personal Top 10, others are not. Some are small eccentric gems which didn’t generate any real buzz - although I did my best to point the way towards them. The list is not ranked. All of these caught got my attention in 2023.

Revoir Paris (d. Alice Winocour)

Alice Winocour’s Disorder was one of the best films of 2015, and when I recommend it to people nobody’s even heard of it. This must not stand! Revoir Paris is equally intriguing and intense, thoughtful and perceptive. The wonderful Virginie Efira plays Mia, a survivor of a terrorist attack in Paris (clearly inspired by the 2015 attack at the Bataclan theatre). Mia can’t remember the attack (in which she lay on the floor among dead bodies, pretending to be dead herself). The blank spot in her memory haunts her. Efira’s performance is devastating. She’s so good. Winocour pays close attention to sound design in her films, and the sounds in Revoir Paris are eerie and distorted. Mia, dissociated from her own reality, can’t filter out background noise, the clink of cutlery, nearby conversations, all infringe on how she hears (or doesn’t). The sound design helps create a visceral sense of Mia’s PTSD. Revoir Paris is about how we understand our traumas, and how important it is - and how difficult - to get busy livin’, or get busy dyin’.

R.M.N. (d. Cristian Mungiu)

For months R.M.N. was my favorite film of the year. Then came Fallen Leaves… Lists show their silliness in such moments. One is not lesser than the other. Ranking is not my forte! I look forward to Christian Mungiu’s next film as though they are dispatches from a wartorn front. 4 Months, 3 Weeks and 2 Days, Graduation, and Beyond the Hills … grapple with a realities so palpable you can smell the dank hotel room in 4 Months, you can feel the icy wind in Beyond the Hills. They’re horror movies. R.M.N. takes place in a hardscrabble little town, ignited by xenophobia and racism. We’re not talking microaggressions. We’re talking arson, death threats. The mysterious opening scene lets you know right away something is not right. R.M.N. shows how “civilization” is a thin veneer. The final sequence of the film was so unnerving I could barely watch. It felt like evil had been unleashed on this small patch of land, terrorizing the very air, molecules cringing away from the disturbance. There’s one standout scene where the village gathers for a town meeting. The people debate, argue, threaten … and Mungiu films it in one take from one angle. It’s got to be a 20, 25-minute scene, with forty speaking roles. This is a real event unfolding in real time. Mungiu’s themes are social, political, religious, personal, problems screaming to be addressed. The situation could not be more urgent. RMN is the best How We Live Now film of 2023.

Fuck Me, Richard (d. Charlie Polinger and Lucy McKendrick)

Fuck Me, Richard is Brief Encounter for 2023. And it gets the job done in 14 minutes. The film is gorgeously shot and beautifully acted by Lucy McKendrick, who also wrote the script and co-directed. I wrote about Fuck Me Richard here on my Substack.

Fallen Leaves (d. Aki Kaurismäki)

Two lonely flawed people find themselves in each others’ orbit. And what a fragile orbit it is. Holappa (Jussi Vatanen) works in construction and keeps getting fired because he’s an alcoholic. Ansa (Alma Pöysti) works whatever odd jobs she can find, trudging home after work to her quiet apartment. Fallen Leaves is a romance, not a raging inferno but a weak flickering flame. It’s an effort for these two to connect. Kaurismäki’s eye is gentle and comedic, his framing eloquent and evocative. The larger world comes to this quiet Helsinki world as a far-away echo: Ansa sits at her kitchen table and listens to reports on Russia’s invasion of Ukraine on the radio. Maybe it’s too much work to bridge the gap between herself and Holappa. And maybe that’s not a tragedy. Solitude has its comforts. And maybe romance, supposedly a high watermark of the human experience, offers no comfort at all. But maybe it does.

Pinball: The Man Who Saved the Game (d. Austin and Meredith Bragg)

I loved this one so much, and was gratified to see Richard Brody’s review at The New Yorker. We discussed it at one of the NYFCC meetings, bonding on how much we appreciated the film. The film does not have massive ambition. It doesn’t try to position the fight to save pinball as an event with wide-ranging consequences. The film exposes a forgotten little slice of history, and it does so with panache, humor, and freedom. It’s quirky without making a fetish of it. It’s played for real. These people seem like real people. The romance is convincing and surprisingly deep. In the good old days, Pinball: The Man Who Saved the Game would have had a nice theatrical run, and more people would have seen it. Seek it out. I reviewed Pinball: The Man Who Saved the Game for Ebert.

The Beasts (d. Rodrigo Sorogoyen)

The Beasts unfolds horribly, inevitably, like a nightmare. A French couple, Denis Ménochet and Marina Foïs, move to the hill country of Galicia, to farm, and live close to the land. They were successful city people, until finally they had enough. Farming is tough work, but they are together in it. The couple is vaguely aware that the people living there are not too thrilled about outsiders coming to the land they’ve lived in for generations. It’s even worse because hill farming is falling into obsoletion. Times are tough. The old ways have changed. “Not thrilled” is eventually revealed as active hostility. Blind rage, really. The neighbors wage a war of sabotage on the French couple’s farm: polluting their well, urinating on their tomato plants, threatening them physically, following them, being truly alarming. The feeling of claustrophobia and paranoia, of being closed-in on all sides, is palpable. The eventual confrontation is truly shocking, but the film doesn’t stop there. What happens afterwards cracks the story open into far more complicated themes, of obsession, letting go, and the complicated relationships between adult children and their parents. I couldn’t shake off the effects of The Beasts for a couple of days.

Holy Frit (d. Justin S. Monroe)

There are documentaries covering far more pressing subjects than a glass company making the largest stained glass window in the world. But this one was so deeply satisfying! I love movies about process, I love movies about competence. Also I knew nothing about the subject of stained glass and I loved learning more. The stained glass studio in question is populated by dedicated artisans devoted their lives to a 1,000-year-old artform. There’s something hopeful about this. Also hopeful, and soothing, is watching people so good at what they do, who spend their time DO-ing and creating, problem-solving, collaborating. I adored Holy Frit and I reviewed for Ebert.

Asteroid City (d. Wes Anderson)

The stranger Wes Anderson gets the better, as far as I’m concerned. The French Dispatch, which I loved, alienated a lot of people, and frankly, I get it. The film is nostalgic for The New Yorker in the days of Harold Ross’ editorship. I mean, this is not exactly a mainstream interest. In The French Dispatch, Anderson went as far as he could go into his own niche style, pushing it out even further, until it abstracted. A lot of times I hear people criticizing a filmmaker for the very thing that makes them THEM. Baz Luhrmann comes to mind. I hear the criticisms and think, “So you basically want Baz Luhrmann … to stop being Baz Luhrmann? Would you be happy if he made a quiet intimate drama? And be like everybody else?” Asteroid City is highly-stylized, overtly artificial, but it pulses with a very real heartbeat. At this point, The French Dispatch, is my favorite of Anderson’s films, but Asteroid City captivated and moved me.

All Dirt Roads Taste of Salt (d. Raven Jackson)

Raven Jackson’s All Dirt Roads Taste of Salt is an extraordinary directorial debut. You have to see it to understand how radical it really is, how singular. I wrote about it for Rogerebert’s Top 10 of 2023.

The Killer (d. David Fincher)

The film opens with the killer (Michael Fassbender) setting up a stakeout in an abandoned WeWork office (lol). He waits for the right moment to kill his prey. In voiceover, he tells us how to be a killer, the mindset it requires. Then comes the moment for him to fulfill his mission and … he screws it up. After all that voiceover meditating on your job and how great you are at it, the big moment comes and you flub it? This is just one of the many sneakily funny moments in The Killer. My cousin Kerry O’Malley is in it! She has a crucial big scene with Fassbender, and she crushes it. Michael Fassbender and Carey Mulligan shout her out by name in their Actors on Actors conversation.

Reality (d. Tina Satter)

An excellent directorial debut. Reality is an adaptation of the successful stage play (also directed by Satter), the script made up entirely of the FBI interrogation (excuse me: “interview”) of whistleblower Reality Winner. The actors (Sidney Sweeney, Josh Hamilton and Marchánt Davis) are all terrific, as they recite the FBI transcript word for word, including “Uhms” and “uhs”, awkward phrasing, trailing ellipses … and yet all of it leaps off the page. It’s fascinating to me how well it works. I reviewed Reality for Ebert.

The Unknown Country (d. Morrisa Maltz)

Lily Gladstone is having a year. She’s getting all the flowers for Killers of the Flower Moon, but her quiet grounded performance in An Unknown Country - where she is in every scene, every shot - is a revelation. She is so present. This is what made her performance in Certain Women so attention-getting. Gladstone is an amazing receiver. In The Unknown Country, you watch her receive the world, other people, atmospheres, locales. You watch thoughts flicker across her face. I was so happy the Gotham Awards gave her Best Lead Performance for The Unknown Country. I reviewed The Unknown Country for Ebert.

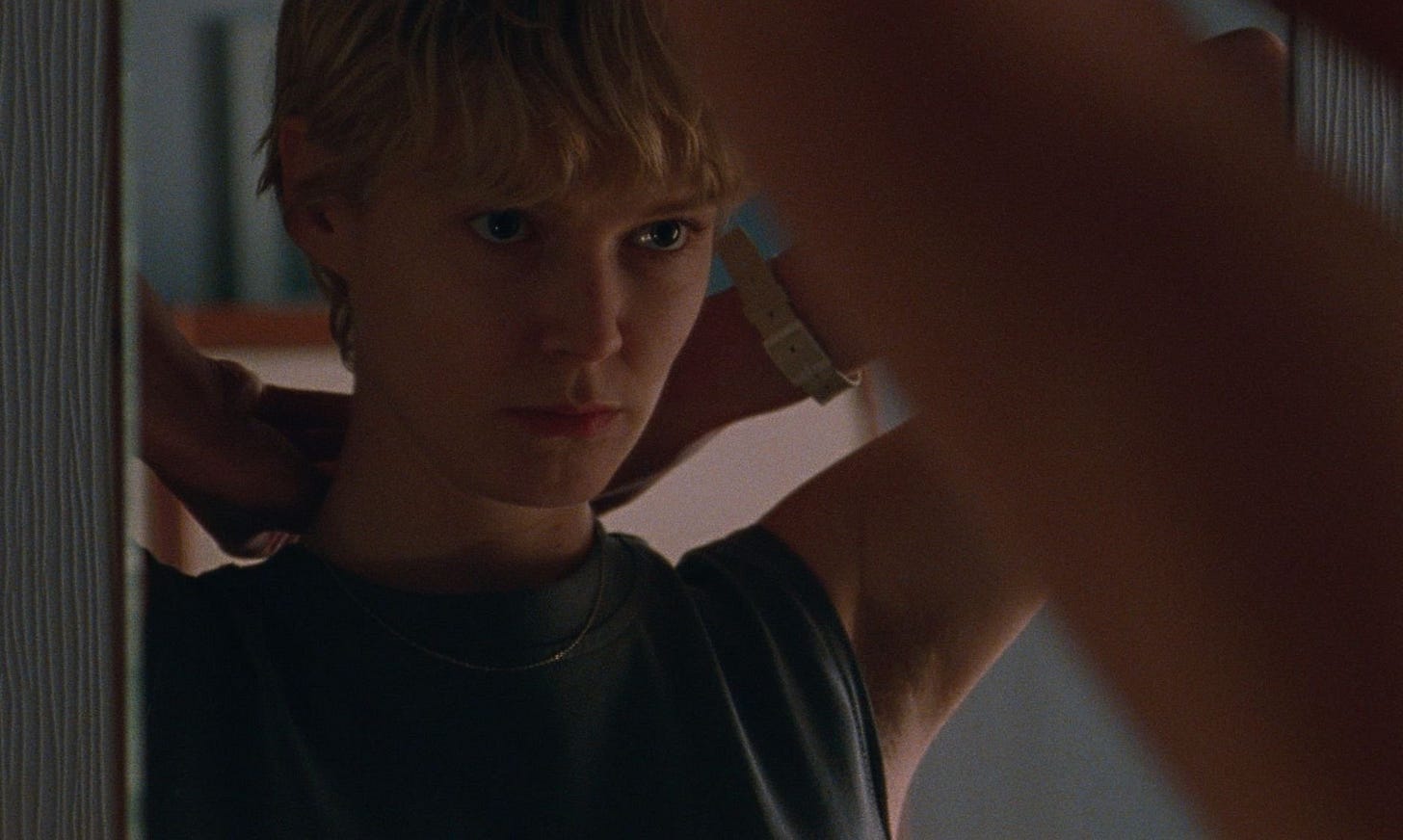

Scrapper (d. Charlotte Regan)

Scrapper - another amazing directorial debut from a female filmmaker (2023 was full of those) - is on my personal Top 10. The film was touching, but it has teeth. I’ve seen it compared - unimaginatively - to last year’s Aftersun, I guess because it’s about a father and daughter. Recency bias is a thing. Aftersun is great, but Paper Moon is a much better reference point for Scrapper. Amoral little girls with con-artist sensibilities: we need more of those! I reviewed Scrapper for Ebert.

20 Days in Mariupol (d. Mstyslav Chernov)

This hair-raising film is the only proper choice for best documentary of the year. It’s difficult to watch - even unwatchable at points - and it should be hard to watch.These people have to actually live through it. Or not. And Chernov is on the ground, watching tanks roll in, hiding from gunfire, trying to find a spot in the ruins where he can grab a Wifi signal to project the images out into the world. Some great documentaries this year but … none of those filmmakers were busy dodging bullets as they made their films. None of these films are 20 Days in Mariupol. No contest.

A Thousand and One (d. A.V. Rockwell)

Add this to the list of extraordinary debuts from women filmmakers. A.V. Rockwell wrote and directed this painful beautiful story about a woman who kidnaps her son out of the foster care system. She claims him back. She’s living in a women’s shelter, passing out fliers offering her services as a hair dresser, trying to get her life in order after some time in prison. She’s got no way to support her son, but she doesn’t think about that. He’s being abused. She’s got to get him back. Teyana Taylor, known mostly for her music career, gives one of the best performances of the year.

Blue Jean (d. Georgia Oakley)

Up there, for me, with R.M.N. and Fallen Leaves. And yet another directorial debut from a female filmmaker. I think we need to acknowledge this, strongly, loudly. Movie releases are so different now. Things go to streaming services and vanish in the confusing algorithms. You can’t find anything. Georgia Oakley got interested in the Section 28 laws, passed in 1988 in Margaret Thatcher’s England, forbidding the “promotion of homosexuality”. These laws were maintained until 2003. Blue Jean takes place in the late 1980s. High school phys. ed teacher Jean (Rosy McEwan) lives with the valid fear of being fired if her sexual orientation is discovered. She has a girlfriend, lots of lesbian friends, but must hide it. The tension is actual but psychological as well. There’s a lot of pain in this film, pain and helplessness. Rosy McEwan gives one of the best performances of the year.

Killers of the Flower Moon (d. Martin Scorsese)

I can’t stop thinking about Robert De Niro’s performance, one of his very best.

Fair Play (d. Chloe Domont)

In the olden days, Fair Play would have been in the theatres for 3, 4, 5 weeks, could have gathered momentum, with people reading reviews, and deciding to go check it out. There was just more time “back then”, i.e. 10 or 15 years ago. Time for a movie to get the attention it needed: give it a chance, for God’s sake. When you turn movies into “content”, you lose motivation to create anything lasting. It’s on to the next piece of content! Whatever is featured on the main page of a streaming service has to be swapped out on the regular. Movies become disposable. Fair Play got very good reviews. It works on every level it needs to work. Phoebe Dynevor and Alden Ehrenreich play a couple working at the same financial firm (and keeping their relationship a secret). They are happy. Until she gets a promotion. The very promotion he was hoping for. Ugliness spills to the surface. It’s a workplace-romantic drama, tension coiled tight, so tight it seems to be a legitimate “thriller”, where bunnies could potentially be boiled at some point. But no: this film is really ABOUT something. It’s telling some dirty little secrets, secrets we all know, but are afraid to say. Aren’t we PAST all this? Well, no, we aren’t. So let’s look at it, let’s talk about it.

Afire (d. Christian Petzold)

Christian Petzold has often dealt with the legacies of World War II/Communism on Germany, and the uneasy process of integrating East and West Germany following the fall of the Berlin Wall. Afire is seemingly a small story - almost cliched - about a frustrated writer trying to finish his new book, derailed by procrastination. His editor doesn’t like the new book. The writer is an unpleasant personality, envious, recessive, passively hostile. On a weekend retreat, the writer descends into an almost somnambulist state. Petzold presents this, on the surface, as if it is a normal story about one man dealing with his creative process. But … but … there’s a nearby forest fire, only perceivable by the glow in the sky … just over there. Nobody feels alarmed. It’s over there, after all, not here. The forest, though, is filled with random shrieks, animal cries, sudden rustlings in the trees and grass. The animals know. The animals know to be afraid, to run for their lives. What is wrong with humans that they stay put, ignoring the imminent danger?

Emily (d. Frances O’Connor)

Recency bias is in evidence when films that came out early in the year get lost in the shuffle. Emily is yet another directorial debut by a female filmmaker, and I went into it skeptical and resistant. Emily Brontë is a mysterious figure, the most mysterious of the Brontë sisters (and brother Branwell), so how would this mystery be treated? Would Emily be reduced to cliches? Would the film try to explain her? Well, yes and no. The enduring question is how could this inexperienced reclusive woman write as MAD book as Wuthering Heights? Emily doesn’t try to answer these questions, necessarily, although it does take a speculative approach. What if … what if … Emily Brontë is still surrounded by choruses of whispered rumors over 200 years after her birth! Madeleine Olnek explored many of the rumors surrounding Emily Dickinson’s life in the wonderful Wild Nights with Emily and I’d put Emily in a similar category. O’Connor doesn’t declare “This is the truth.” She investigates the subject matter in an imaginative way. Charlotte Brontë fans (of which I am one, most passionately) may balk at the portrayal of Charlotte here, but again … this is all speculative. It’s all subjective. How did the world appear to Emily? We just don’t know. O’Connor wonders Maybe it was something like this. I found Emily a fascinating jumping-off point. I reviewed for Ebert.

May December (d. Todd Haynes)

The circumstances in Todd Haynes’ May December are so sordid you recoil from it as you’re leaning in to catch as much as possible. The destabilizing situation is destabilized even further by the introduction of an outsider, an actress (Natalie Portman), who infiltrates the messed-up family to do “research”. What on earth is she up to? I’ll go ahead and answer that. This broad is up to no good. May December is a story of doubling, and doubling requires dissolved boundaries, something Gracie (Julianne Moore) knows a lot about. Denial is a powerful drug. There’s a scene in a clothing store dressing room I can’t shake off, no matter how hard I try. I reviewed May December for Ebert.

Sanctuary (d. Zachary Wigon)

I really liked Kurt Loder’s reivew of this two-hander, written and directed by Zachary Wigon (whose Heart Machine has haunted me ever since I saw it). Margaret Qualley and Christopher Abbott meet in a hotel room, and their relationship shifts and slides and transforms, sometimes violently, sometimes imperceptibly. Everything is in flux, everything is up for grabs. They are role-playing, after all. Or are they? Each struggles for control over the other. Both actors go places a lot of actors hesitate to go: this stuff is ugly, but it’s also really really funny. I could not predict what either of these characters would do. I’m always excited when a movie comes along featuring just two people talking to each other. But there’s nothing “just” about it. Enough with spouting “Show don’t tell” as some ironclad rule. Art has no rules. Tell stories the way you want to tell them.

Everything Went Fine (d. François Ozon)

An “issue” film with real pathos. An elderly father, incapacitated by a stroke, asks his daughter to help him die. There are ethical and moral issues at play, of course. What he is asking her to help him do is illegal in France. You have to get creative. But this is no Very Special Episode. The prolific Ozon and his gifted cast focus on the personal: grief and loss, grappling with a complicated past, a family still arguing about what the past even WAS. Any movie featuring Charlotte Rampling and Hanna Schygulla in small roles is well worth a look! Legends! I reviewed for Ebert.

Boston Strangler (d. Matt Ruskin)

Boston Strangler is so good it would have generated a lot more buzz if it had been in the theatres circa late 90s early aughts. Stephanie Zacharek's review in Time inspired me to check it out. Two female reporters (Carrie Coon and Keira Knightley) maneuver in a world where they are the only women. The feminist aspect is there, but not underlined. There are no girlboss monologues. I am so sick of girlboss monologues. The women, one a veteran, the other a rookie, are forced to work together on the Boston Strangler case. They are aware that their collaboration is a gimmick, almost a joke: Check out these two girls working a crime case! But they, of course, take their work very seriously. Refreshingly, they don't become BFFs, they don't get drunk and dance in a bar to show they're bonding, although they do meet up in a bar after a tough day to have a drink, just like their male colleagues. They don't bond "as women". They bond as colleagues who happen to be women. They're both ambitious workaholics. The stakes are high. Nobody expects much of them. Even their conversation about "how on earth do you manage raising kids while doing this job?" is on a practical level, it’s the way women actually speak to each other. Boston Strangler is a procedural, but it’s a procedural along the lines of Memories of Murder or Zodiac: it’s interested in how cases like this infect the people working it. The mystery cannot be compartmentalized, and at a certain point the investigation becomes obsessive monomania. Very satisfying film. Unfortunately lost in the shuffle of the year.

Little Richard: I Am Everything (d. Lisa Cortés)

I needed a documentary like this in the wake of Little Richard’s death. I needed a place to put all that feeling of loss and tribute. I was thrilled I got to review Little Richard: I Am Everything. It was an opportunity to put some of my feelings about this gigantic figure - the self-proclaimed “architect of rock ‘n roll” - into words.

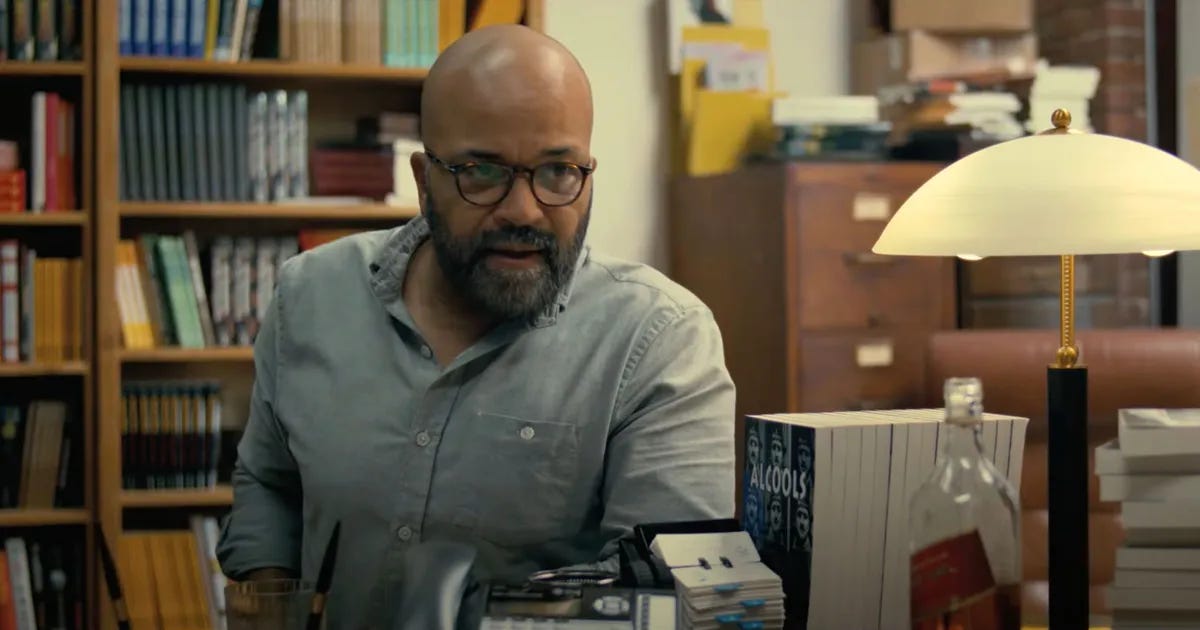

American Fiction (d. Cord Jefferson)

Jeffrey Wright is - and has been for years - a national treasure. He has one of the best voices in American cinema and theatre. The deep resonance of his voice can be used to dramatic effect or comedic (see Asteroid City). He works with such intelligence and control. American Fiction is often hilarious, telling truths everybody knows, but might be afraid to say. It’s satire, but it’s satire as satire should be: it’s so close to reality, cuts so close to the bone, that maybe some people won’t even “get” that it’s satire. What I found particularly amazing, though, about Cord Jefferson’s approach (in what is yet another impressive directorial debut), is that with all the hilarity and absurdity … American Fiction also manages to be a heartbreaking story of a man finding his way towards his true self. The family relationships are acutely observed. The romance is handled with such delicacy. It’s very human. Two grown-ups meeting each other, baggage intact, but having been through enough in their lives they can actually speak their feelings, express their needs. There’s a hybrid quality to American Fiction, a free mix of humor, ridiculous, authentic depth of feeling. Not to be tried by amateurs!

The Taste of Things (d. Tran Anh Hung)

I was actually surprised at how emotional The Taste of Things was, how much it touched me. The film features gorgeous food, of course, so beautiful-looking my mouth watered. I loved how the film focused on process as much as result. The meals when they reach the table are masterpieces. Back in the kitchen, though, it’s piles of vegetables, a chicken being prepared, a broth carefully poured through a sieve. The opening scene is 38 minutes long and shows the preparation of one meal. Why is this so quietly riveting? I think because what we are seeing is two characters (Juliette Binoche, Benoît Magimel) devoted to excellence, to creation, and - most of all - to collaboration. They don’t even need to speak to one another when they’re in this state. It’s a thrilling mind-meld, the basis of their relationship. There’s romance in The Taste of Things, patiently presented by these two gorgeous actors, allowing us time and space to get to know them, to understand how much they mean to one another. I was brought to tears on more than one occasion. I reviewed The Taste of Things for Ebert, and was so happy it gave me the opportunity to include a quote from American food writer M.F.K. Fisher. It applies. Food isn’t how you show love. Food IS love.

And that’s it for now!

I would love to hear from you: what movies have you loved this year? What movies touched you, made you laugh and/or think? What surprised you? What took you off guard?

Thanks so much for subscribing. Your support is appreciated!

FALLEN LEAVES is playing in Seattle next month at the theater I volunteer at, so I'll be sure to check it out. Of the few movies I saw that came out this year, WE KILL FOR LOVE was a pleasant surprise and my favorite of the bunch.

I absolutely cannot work out why The Beasts isn’t in every best of list like Anatomy of a Fall is. Why I didn’t hear about it until the end of the year. Loved it. Great article.