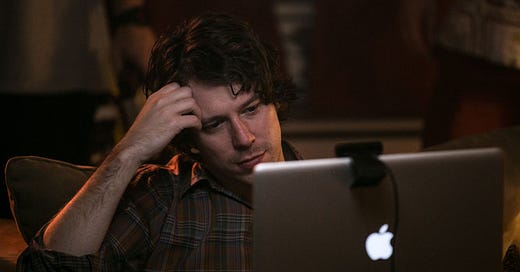

Obsession is the landscape of Zachary Wigon’s feature debut, The Heart Machine—obsession so strong it obliterates everything in its path. Obsession has its own logic, isolating those in its grip. Vision narrows to a pinhole. At its best, The Heart Machine re-creates that state of mind, mostly through a very unnerving performance by John Gallagher Jr.

The Heart Machine resists the impulse to make a statement about How We Live Now, despite its storyline about online dating and intimacy via Skype. It isn’t about the dangers of the Internet, or “catfishing,” or the supposed unreality of online relationships. It’s more reminiscent of Vertigo, with shades of Blow Out and The Conversation, the film operates in the airless bell-jar world of a man convinced there’s more going on than meets the eye. Except for its tension-deflating ending, The Heart Machine is an unblinking - at times excruciating - look at one man’s unraveling.

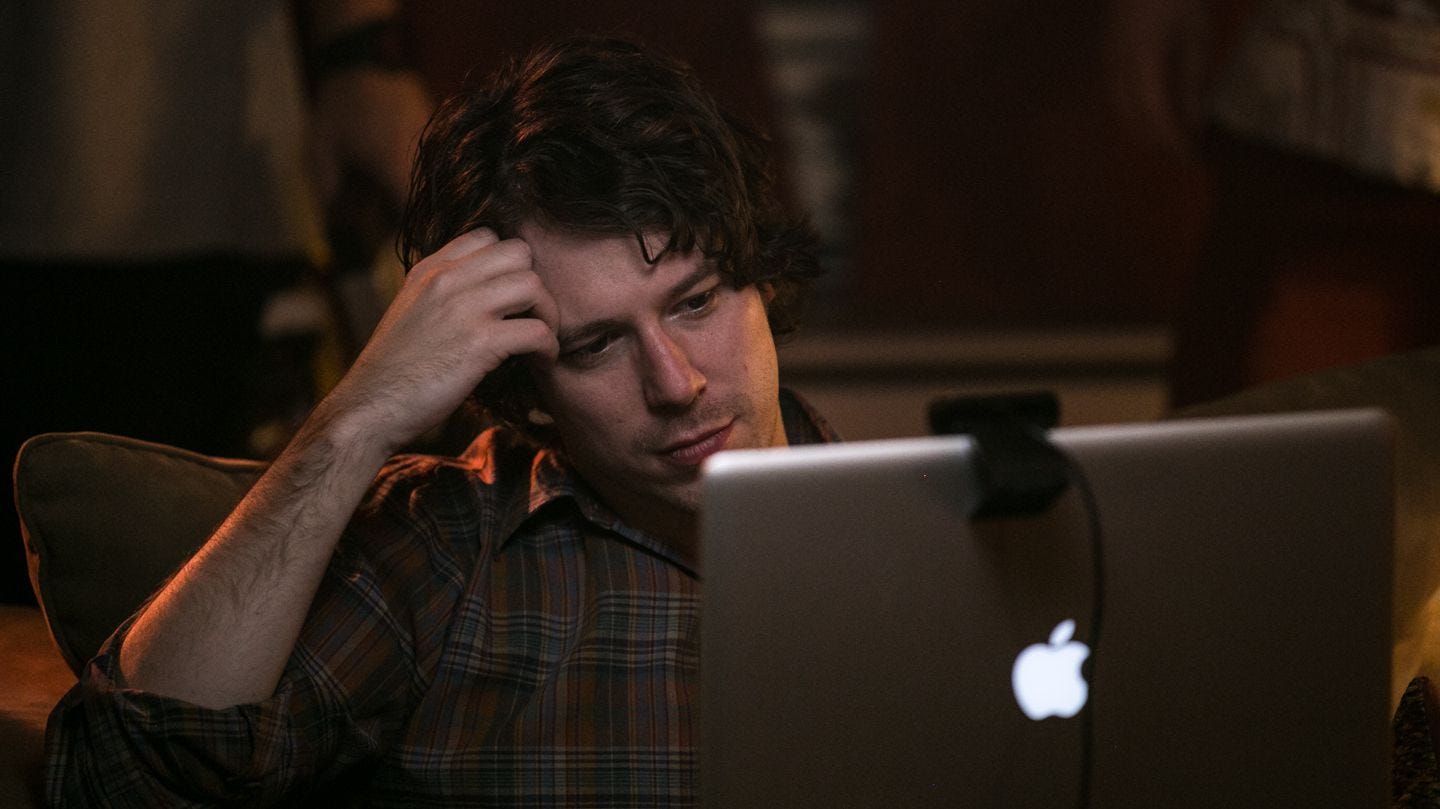

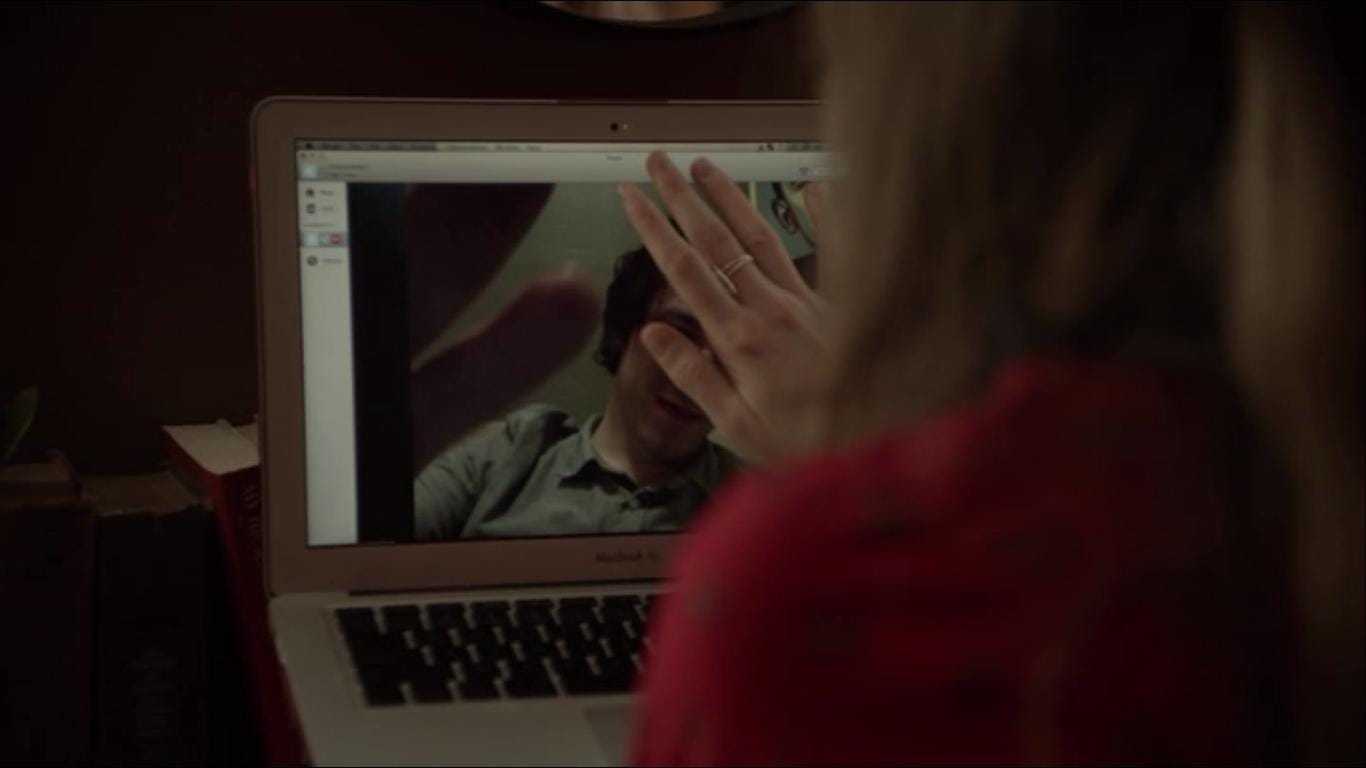

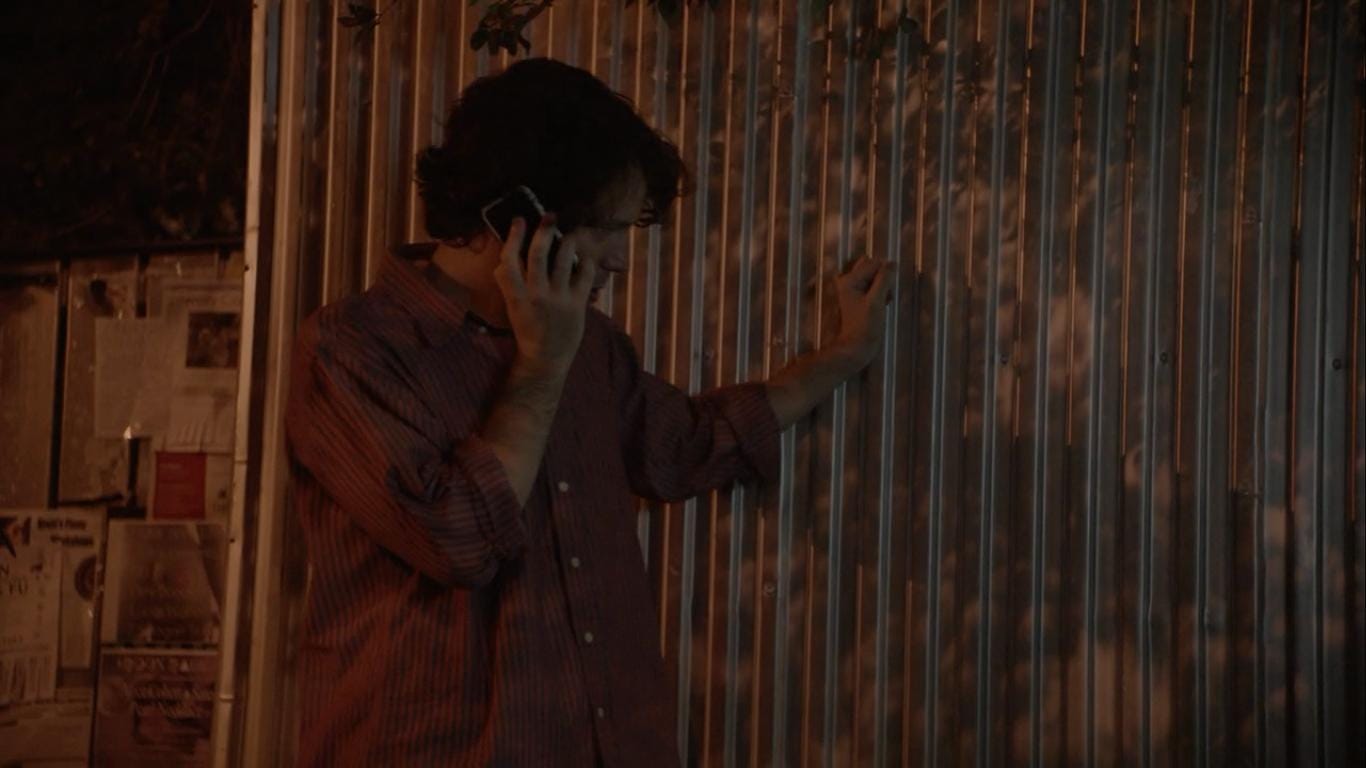

Cody (Gallagher) is first seen huddled over his phone in a nightclub, surrounded by writhing dancers. Later, back home, he signs on to his computer for a conversation with a woman named Virginia (Kate Lyn Sheil). From the tone of their conversation—-tender and sweet, humorous and intimate-—it’s clear they are enmeshed in each other’s lives. She’s in Berlin on a six-month writing retreat; he lives in New York. They haven’t met yet, but they’ve been Skyping for months, and looking forward nervously to her eventual return to New York, when they can finally meet in person. Both express relief at having found someone so nice, so simpatico, in the wilderness of the New York dating scene.

Wigon (who also scripted) withholds a lot from the initial presentation, and The Heart Machine provides snippets of further information through behavior fragments and what appear to be flashbacks, presented as though they could be current, adding to the psychological disorientation. One day, on the train into Manhattan from his apartment in Bushwick, Cody sees a girl reading a book. Later that night, Skyping with Virginia in Berlin, he says to her, laughing, “Hey, it’s so weird, but I saw your doppelgänger today on the train!” Virginia doesn’t appear interested and changes the subject.

Cody starts to suspect Virginia isn’t in Berlin at all, and never was. He suspects she’s lying to him for some reason. He pins a collage of “clues” up on his closet wall—-subway maps and marked-up street maps-—making him look like a homicide detective working a case, or a serial killer tracking his next victim. He analyzes the background noises in her Skype messages, isolating barking dogs or the sound of sirens. He pulls up sound clips of German ambulances to compare. He takes screengrabs of her electrical outlets in the background-—outlets that appear suspiciously American. He neglects his freelance writing work and haunts the streets of what he has deduced to be her neighborhood (via her Facebook photo), asking people if they know her, or have seen her recently. Cody, in other words, is becoming unhinged.

There are excruciating scenes where he weasels his way into her peripheral life, chatting up a guy in her neighborhood who works at a coffee shop, manufacturing reasons to keep the conversation going, or, worse, attempting to hook up with someone who’s Virginia’s friend on Facebook. His intensity puts people off. Cody seems like a nice guy, but his behavior throughout The Heart Machine isn’t nice at all. Gallagher is brilliant at suggesting Cody's inner conflicts: he knows he should stop this madness, he knows he is freaking people out, knows he should just ask Virginia what the deal is, but he can’t stop himself. The girls he hooks up with are all Virginia doppelgängers, with long, straight brown hair and similar features. His dates lose their distinguishing characteristics, taking on a monolithic sameness.

Traveling on what appears to be a contemporaneous track, although Wigon eschews a linear structure, Virginia circulates through New York, seeking sexual hookups via Craigslist or Blendr. She finds it all depressing, yet she keeps doing it. Sheil does an amazing job of creating a character perceived mainly through Cody’s eyes. She’s warm and sweet over Skype, yet this doesn’t match the glimpses given elsewhere when she is alone. Is she even real? Has Cody just made her up?

The Heart Machine is stylish and effective, by turns moody or harrowing, grounded in reality or sparked by phantasmagorical psychological torment. Rob Leitzell’s cinematography captures New York (it’s a wonderful New York film,) showing the city in its diverse moods, its jostling humanity, its empty dawn sky, the strange no-man’s-land of subway tunnels at night, and the free-for-all feeling of the East Village at 1 in the morning. It’s New York as alienating metropolis-wilderness but also New York as small town. There are a couple of eye-catching almost 180-degree panning shots, from Cody’s point of view, as he looks up and down a street, or around an unfamiliar apartment. The camera circles, picking up nothingness, the intervening walls, dizzying as they spread out before him. Cody can’t see what’s at the end of that street, or behind that wall, but his eye follows. He can’t help himself.

Unfortunately, The Heart Machine doesn’t fully hold together as the truth emerges. The tension, so uncomfortable throughout, evaporates. Cody says at one point that it’s weird to have not met Virginia yet, to have “so many feelings tied up in something so far away.” The sense of distance, not just geographical, but emotional, creates a mindset of frightening isolation and paranoia. This is where The Heart Machine has its greatest impact.

THE REVEAL: (SPOILER)

So what’s the deal with Virginia? No, she was never in Berlin. She was in New York all along. In a flashback to her first Skype interaction with Cody, he asks if she wants to meet in person, and she says, hesitating for a second, that she’s actually in Berlin, and won’t be back in New York for six months. She’s clearly lying. She asks if they can keep meeting online to talk, since obviously they’ve hit it off. No pressure, no commitment, no weirdness, just talk, until she returns? Cody is taken aback, but he agrees.

At the end of the film, Virginia shows up at Cody’s door in the middle of the night, and the two finally meet. By this point, Cody is an absolute wreck. He’s destroyed his life because of his obsession. He’s about to lose his job. He’s covered an entire wall with “clues.” He can barely look at her. She’s loomed in his head for so long, a spectral idée fixe, it’s hard to deal with her actual corporeal self. She says she doesn’t know why she lied, but every relationship she's had ended badly, and she wanted to try something new with him. She liked him so much. She wondered if enforced distance would give their relationship a healthier rhythm, activating the brain, taking sex off the table. She was trying to force a new pattern on herself, using Cody as an unwitting participant.

Wigon is to be commended for not trying to create some artificial thriller twist where Virginia is actually a 72-year-old pig farmer in Iowa. His script is about loneliness and obsession, about two people finding comfort in connecting every day over Skype, about the yearning for real intimacy. Cody and Virginia have both invested in their bond. But Gallagher’s urgent, visceral performance makes the stakes so intensely high, revealing such deep disturbances in his psyche, that Virginia’s reveal feels banal by comparison. Gallagher reveals something in his performance, a man almost as frightening as Travis Bickle, with the same meek demeanor, the same quietness and passivity, the same seething whirlpool underneath. It is not difficult to imagine Cody taking violent measures to make his torment end. What’s frightening is the whirlpool was in him all along. It’s not in everyone. Not everyone goes off the rails like this. What is in him already? Pushing him to this destabilized place?

Could Cody tiptoe his way back into normalcy, could he “let go” of his months of mania, and start up a normal everyday relationship with Virginia? It’s impossible to picture.

The main takeaway is that not only is Cody not okay, he is never going to be okay. He’s gone too far out from the shoreline. There’s no way back.

This was originally published on the now-defunct The Dissolve, October 22, 2014.