The memory-collage of Christmas Eve in Miller's Point

“We look at the world once, in childhood. The rest is memory.” — Louise Glück

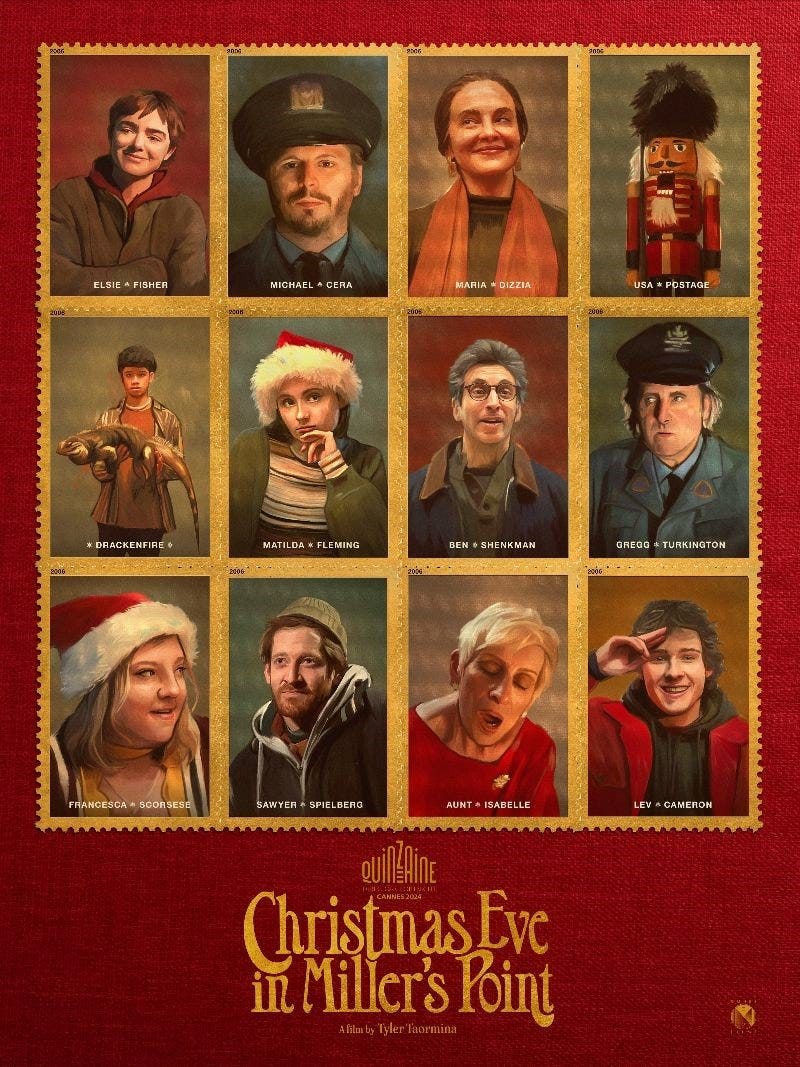

I had no idea what I was getting into when I settled in to watch Christmas Eve in Miller’s Point, Tyler Thomas Taormina’s new film. What I knew about it was from Richard Brody’s review in The New Yorker, and Miriam Bale calling it one of the best movies of the year on Instagram. Intriguing, particularly Brody’s description of how it presents the holiday family genre in a new way: “it … provokes bracingly complex emotions and frames them in the snow-globe-like quotation marks of reminiscence”. My goodness. Bump it to the top of the list.

A big Italian-American family gather together for Christmas Eve. It’s the early 2000s, judging by the “cell” phones among the teenage population. Four generations are present. The noise is deafening, the table buckles with the meal laid out, and the side conversations occur sotto voce , often overheard in fragmentary voiceover as the camera drifts over the decorations, the food, giving a strange almost dissociated experience of what is an intimate family gathering. Other more cliched holiday comedy-dramas unfurl as though they are in real time, and you are thrust into the middle of the family dynamics. Nostalgia is implicit, but it comes from the viewer only, caught up in their memories. Here, the nostalgia is in the presentation. It’s like remembered conversations, and also the sensorial memory of the noise, smells, perfume, hairspray, cologne, of gatherings from long ago. The “question marks of reminiscence” is in the form itself.

The style is introduced from the jump, where houses glimmering with colored lights float by outside a car window, reflected upside down. The upside-down-ness of it is a hint of things to come, the upending of genre expectations. The “experiments” in style continue throughout, starting with the voiceover-voices, disconnected (often) from their bodies - we hear them, but we are not zoomed on them … this calls to mind Robert Altman, where his big group scenes often involved miked actors, in character, having no idea whether or not the camera was on them.

A family is in the car on their way to the gathering. There’s dad Lenny (Ben Shenkman), mom Kathleen (Maria Dizzie), teenage daughter Emily (Matilda Fleming), and younger brother. Kathleen sits in the back seat, already in a state of irritation and hurt at her daughter’s checked-out contempt/over-it personality, all of which seems directed at her personally. You can read into this. Emily is in puberty. Kathleen misses the engaged happy child. It happens.

They arrive with the party already at its peak. A flurry of hugs, kisses, exclamations of surprise, as though they hadn’t just seen each other last week. They are absorbed into the group. The cousins all race off with each other, the little kids in Christmas outfits, the older teenagers retreat to the basement to play video games. Francesca Scorsese plays Michelle, a cousin the same age as Emily, and they settle right in to talk to each other. They have known each other since they were babies.

Scenes are not played out in an in-depth start-to-finish way. The camera moves on by. You get to know the relationships as though you were a stranger invited to the party and you had to put it together. The adult siblings - Kathleen, Ray (Tony Savino), Bev (Grege Morris), John Trischetti (Matthew) - hole up in one of the kids’ bedrooms to talk about what to do about their mother whose health is failing. Should they sell her house? Sheould she keep living with Matthew? She’s becoming a burden, she requires more care than Matthew can provide. Tempers run high. Assisted living? Ray is adamantly against. She’s their mother, how can they do that? Selling the house is also argued over.

Great-grandmother rides up and down the stairs in her automated chair. She falls asleep in the middle of the gathering, but she’s wearing her Christmas sweater and a beloved member of the family.

This family has rituals. There’s a Secret Santa gift exchange. There’s a group walk to the end of the block to see the holiday-decked-out fire trucks, complete with a real-life Santa tossing candy down to the crowds gathered. There’s also a long walk, everyone bundled up, paired off, having conversations small and large.

Meanwhile, Emily is itching under her mother’s control. She can’t do anything right. She sneaks out to meet up at a local diner with her group of pals. Michelle comes. There’s a shoplifting expedition. There’s a silent scene where couples pair up and go to their respective cars to make out, or not. The snow covers the car windows, leaving the couples in a disconnected quiet utopia.

The adults have rituals. The kids have theirs.

There is an ongoing side bit with two local cops - Michael Cera (who also produced) and Gregg Turkington - who shrug when a car speeds by, who shrug when the diner owner freaks out because the group of kids mess with her dumpster. Their conversations, including a confession later, have a flat-affect tone which, frankly, doesn’t fit with the rest of the film. It feels like a distraction.

But I want to say something about my critique. The “perfect is the enemy of good.” Give me a flawed over-reaching masterpiece, like Megalopolis, or The Brutalist, or Magnolia, over a safely-perfect perfectly-constructed film, the ones that win all the awards. I consider some of my favorite films to be perfect (Only Angels Have Wings), but more and more - in our algorithm “content”-driven world, where eccentric films are lost in the maw of streaming platforms, of ironed-out narratives, complacent styles, of not-rocking-the-boat, of fear-of-social-media-backlash for “inappropriate-ness”, the complete disconnect from sex … I gravitate towards the messy. I am a mess. I like challenging work. I like talented people who TRY things. Go for it. Stretch out. Give it a shot.

So the cops’ flat-affect conversations - disconnected from the Bansano home - comes from another film, or a sketch-comedy. I didn’t care about them.

But the rest of the film is so dazzlingly confident, and almost eerie in its affects, so intimate, with affection and humor and anxiety fizzing through it … who the hell cares about a small thing that might not work? (Others may disagree with me, and of course that’s fine). The film gets all the important things right, and what it gets right is ephemeral, filled with echoes, and an inchoate sense of mortality, loss, memory.

What you sense is that what you are looking at is not in-real-time at all. The film itself is a memory, and a collective one. The conversation about the mother’s house, and the mother’s health, is a harbinger of the future. The mother will die, the house will be sold, and perhaps there will be no gatherings after this, or it won’t be the same. The teenagers will grow up and move away. Perhaps the mother is the glue (judging from her warm behavior, her care for everyone there) and without her things will fall apart. Not in a toxic way but in the natural way time does its work, good and bad.

This made me think of my own extended family. Both the O’Malley family and the Sullivan family are big sprawls. Irish Catholic, you understand. Aunts, uncles, a veritable crowd of cousins, and now the cousins have a crowd of children. We are all close. My cousins are all basically the same age as me. We grew up together. There’s nothing like cousins. (The only story I can think of that actually captures the cousin dynamic is John Irving’s Prayer for Owen Meany.) The level of fun we had … the shenanigans we got up to while the grown-ups drank gin and tonics in the dining room … was thrilling, a fever of mad fun, because we knew our time together was limited. We still reference our jokes from childhood.

But now … unless there is a wedding or a funeral, we don’t gather together all at the same time. We remain close, and social media is where I see what everyone is up to. But the older generation is leaving us. I lost two beloved aunts in 2021. A connecting thread with the past severed. Watching young people grow older.

Christmas Eve in Miller’s Point feels like it’s a family looking back on Christmas Eves past, watching one of the home movies they bust out when they’re together, to relive the good times. There are long shots without people, lingering on the fireplace, the food, the Christmas decorations, probably made by one of the kids, or maybe made by one of the aunts and uncles in their childhoods.

The fire trucks rattling by, decked out in blazing lights, whirling in surrealistic swirls, colors, somewhat portentous music, Santa seen in a disorienting blur towering in the air … the scene is not literal. It’s how the kids will look back on it, remembering it in a wash of colors, the cold air, the mittens, the excitement. Proust was right: memories come through the senses. Lee Strasberg said sometimes you look at a pair of shoes and see your whole life.

There are touches of deep sadness and awkward tenderness (like Uncle Ray’s short story being read aloud to the group, without his consent, read at first in a mocking voice until silence descends on the group, as they realize how full of truth it is). Cousin Brucie (Chris Lazzaro) is an adult, but he’s still a big kid, dancing around in a Santa hat, loud and funny, the class clown, but perhaps to cloak what is missing in his life. A partner. Kids. Stability. The Gen-X anxiety of feeling like you’re in a state of arrested development. When will you gain the certainty of being a grownup? There’s a brief glimpse of him alone, at night, resting his head on the piano. Despair? Or just tired? Emily sees him. She will remember it.

The Bansano family is caught in a slow globe. This will be the last time. Without an explicit word said, you can feel it.

Christmas Eve in Miller’s Point approaches the profundity of the famous final paragraphs of James Joyce’s The Dead, where of course snow is the main character:

From his aunt’s supper, from his own foolish speech, from the wine and dancing, the merry-making when saying good-night in the hall, the pleasure of the walk along the river in the snow. Poor Aunt Julia! She, too, would soon be a shade with the shade of Patrick Morkan and his horse. He had caught that haggard look upon her face for a moment when she was singing Arrayed for the Bridal. Soon, perhaps, he would be sitting in that same drawing-room, dressed in black, his silk hat on his knees. The blinds would be drawn down and Aunt Kate would be sitting beside him, crying and blowing her nose and telling him how Julia had died. He would cast about in his mind for some words that might console her, and would find only lame and useless ones. Yes, yes: that would happen very soon…

One by one, they were all becoming shades. Better pass boldly into that other world, in the full glory of some passion, than fade and wither dismally with age…

Other forms were near. His soul had approached that region where dwell the vast hosts of the dead. He was conscious of, but could not apprehend, their wayward and flickering existence. His own identity was fading out into a grey impalpable world: the solid world itself, which these dead had one time reared and lived in, was dissolving and dwindling…

A few light taps upon the pane made him turn to the window. It had begun to snow again. He watched sleepily the flakes, silver and dark, falling obliquely against the lamplight. The time had come for him to set out on his journey westward. Yes, the newspapers were right: snow was general all over Ireland. It was falling on every part of the dark central plain, on the treeless hills, falling softly upon the Bog of Allen and, farther westward, softly falling into the dark mutinous Shannon waves. It was falling, too, upon every part of the lonely churchyard on the hill where Michael Furey lay buried. It lay thickly drifted on the crooked crosses and headstones, on the spears of the little gate, on the barren thorns. His soul swooned slowly as he heard the snow falling faintly through the universe and faintly falling, like the descent of their last end, upon all the living and the dead.

Shades. They are all becoming shades. The film remembers them as they were, a long long time ago.

I went to bed after watching it, filled with the film’s mood. I woke up at 2:15. I don’t remember my dreams anymore. The bipolar diagnosis killed my dreams. The only time I remember them is when sleep is interrupted. And I suddenly was flooded with the dream I had been having, an elaborate detailed narrative. It was basically a rom-com and I was the star. It was the Hallmark version of Christmas in Miller’s Point. The dream was so much fun! The sparking chemistry, the thrill of knowing romance was in the air, of being noticed and chosen. My first sensation when I remembered the dream was such sharp sadness I could barely breathe. It was old sadness I wasn't even aware was still there. I thought I was done with all that.

I blame Christmas Eve in Miller's Point for the dream, the thrill of the experience followed by the loss of leaving it. Yearning for that feeling I felt. Memories so far away, but no less precious for that.

Williams Wordsworth, famously, said poetry came from "emotion recollected in tranquility." I love Wordsworth but I disagree with him. There is no tranquility in the present, but emotion is recollected anyway.

Sheila dear, your writing dazzles me. Love, The Real Aunt Kate

This is so beautiful. Bless you.