A re-post for Richard Gere’s birthday:

Who we are when we are alone and we feel totally private is worlds away from our social selves. Even extroverts, people who “put it all on the table” out in the social world, probably also stand in their kitchen in a fugue state, eating an entire jar of peanut butter with their fingers … an activity they would never do if someone else was present.

Private moments are difficult to portray and require a different head-space. Actors are used to (and trained to) show emotions normal people subdue or hide. This is part of the job. But creating a “private moment” that feels private? That gives the audience the uneasy feeling they shouldn’t be watching? It’s so challenging that Lee Strasberg designed an entire exercise called The Private Moment.

Perhaps the most classic example of a “private moment” is Robert DeNiro as Travis Bickle, talking to his reflection in the mirror, but there are many more. The genesis of all of them, as far as I can tell, is Peter Lorre’s horrifying child-killer in M manually manipulating his face while looking in the mirror.

DeNiro as Rupert Pupkin, pretending he is talking to life-size cutouts of Liza Minnelli … classic Private Moment. Holly Hunter in Living Out Loud, drunk, in her kitchen, murmuring to herself, lost in a private zone. Sylvester Stallone as Rocky, looking at his reflection and practicing the joke (private moments often involve mirrors) he wants to tell Adrian the next day. The zone of privacy created in such moments is so vast it is impenetrable, a tough feat when key grips and boom operators surround the actor in the least private setting possible. In such moments, the person circles around himself, into himself, an ouroboros of self-reflection, self-concern, self-dramatizing, a fantasist. These private worlds are often grandiose, portraying a fantasy of ease and social comfort. It’s not just ease by itself, it’s ease that is perceived by others. (Rupert Pupkin in the basement is the perfect example of this.)

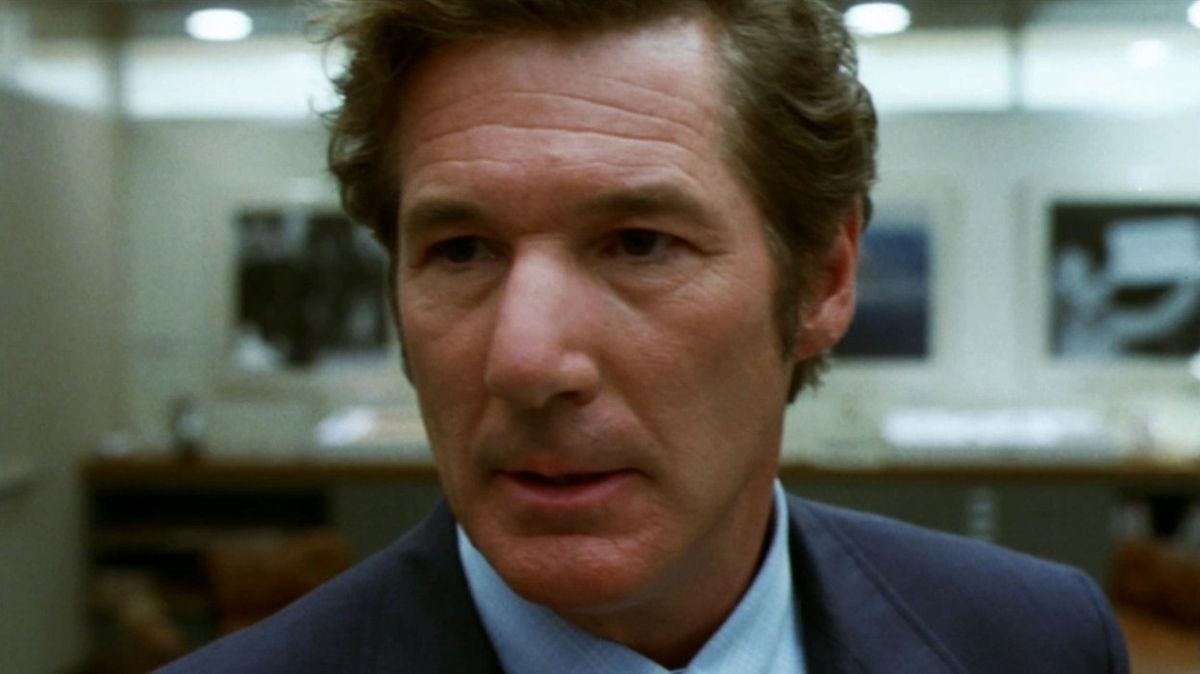

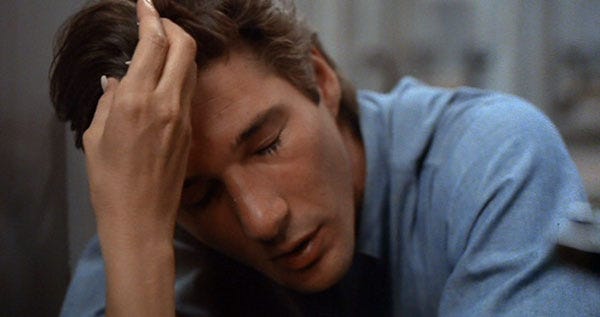

Julian, in American Gigolo, as played by Richard Gere, is all about masks and appearances. His personality has been carefully crafted so his elderly female clients feel special and cared for. When he is alone, he drops the public swagger. There are a couple of scenes showing Julian at home. His home is a fortress of privacy. He is seen working out, listening to Swedish language tapes. One scene in particular is a quintessential Private Moment, and it involves, of course, a mirror.

But Julian’s privacy is more involved than just preening in front of a mirror.

The scene I want to discuss and examine:

A variety of ties and shirts (all Armani) lie on Julian’s bed, everyday objects transformed into glittering possibilities of persona through how Gere looks at them. His is a merciless connoisseur’s eye, but the eye does not obliterate warmth. Every tie, every shirt, opens up worlds in his head. They’re all beautiful. What matters is putting the right tie together with the right shirt. That will take some time. He has to crack the code.

Smokey Robinson sings in the background, “The love I saw in you was just a mirage …” Apt words, since Julian’s dreamspace of persona, of projected self – historically/stereotypically a woman’s realm – is also a mirage. Julian’s whole life is a mirage.

Julian, in his underwear, stands by the bed, looking down at the ties and shirts, considering the combinations, colors, textures. He cocks his head, thinking. He purses his lips after a moment. He seems pleased. There is a unique blend of laziness and focus on his face. He is like a confident athlete or an animal. He is not in a hurry, but his eventual choice is very important.

Sometimes, as he moves the ties around from shirt to shirt, he sings along with Smokey Robinson. “You led me on …with untrue kisses …”, but he appears to be unconscious of the fact that he is singing. This is what happens when we feel private. We don’t sing along to a song like we’re in a karaoke bar. There is no audience. We wander into the song, we wander back out. It’s not performative. It’s something else. Here, the song is all part of his dreamspace of self-absorption. The moment is so private that if someone walked in, he would stop doing what he was doing. He would have to grapple, quickly, for his public persona.

There’s something stereotypically feminine about such private moments of unembarrassed self-regard, which is why they can be so unbalancing and riveting when we see it in a man. In the movies, when women look in the mirror (in public or by themselves), they usually do so to check the perfection of the mask: Powder applied, lipstick applied, how do I look, all still okay? But when men look in the mirror, they attempt to either look behind the mask, trying to see the self, brutalized (and brutal) in the outside world by having to “Be a Man” all the time. OR they look in the mirror to pump UP the mask, to step into a world where they dominate. (Travis Bickle.) It’s a different relationship to Self. (I wrote an entire piece for Oscilloscope about Men and Mirrors.)

Here, Julian is engaged in the same process as a woman looking in the mirror, except that while his mask is being chosen (brown tie with blue shirt, etc.), he also communes with something intensely pleasurable. It’s visceral. He is not analytical. He languishes in possibilities. He wallows in aestheticism. He is outside of Self, outside of Thought. It’s there in the boyish cock of his head to one side as he looks over the ties, the way he purses his lips happily: it’s a moment so vulnerable that no one on the outside has ever seen him this way.

He looks like a kid considering the pedals on his bike or something.

Julian doesn’t look at women the way he looks at those ties, with the same lazy sensual appreciation. With women, he is kind, the kindness originating in extreme knowing-ness. He knows how to make them come. He is proud of this, but not in a cocky way. As a matter of fact, it’s the opposite. He knows how to serve them. Other men are selfish and don’t care. He cares and takes the time. It makes him feel like he’s “really done something”, as he tells Lauren Hutton’s Michelle in Julian’s only introspective monologue. Still, there’s a distance with women, and it is the distance which draws women to him.

The ties, though? He looks at those ties with a satisfaction so deep he’s satiated. Yes, yes, those colors are just right. Just right.

Manohla Dargis once pointed out that Gere’s “gifts as a film actor are located in his body, in his silky walk and fluid gestures.”

True, and when Gere is allowed to incorporate his own natural narcissism into a role, he shines. Narcissism is part of what he brings to the table.

He is not convincing as a conventional romantic leading man. He is too self-centered. He gives himself away in a scene in Pretty Woman where he and Julia Roberts get out of a limo together on an airfield. He gets out of the limo and then just stands there, as she, in her long gown, gets out of the car by herself. It’s an unconscious moment from him, it’s not “highlighted” as a character bit by director Garry Marshall or by him. It doesn’t even occur to Gere to lend her a hand. It would have been interesting if they made more of a point of it.

In its own small way, Richard Gere not helping Julia Roberts out of the limo obliterates the fairy-tale narrative the film is trying to tell.

I am not criticizing the moment. I think it’s FASCINATING. Julia Roberts strolls away with the movie. Gere doesn’t stand a chance. (In a way, his performance in Pretty Woman is the most generous thing he has ever done: he got out of the way to make room for the brand new powerhouse, stealing the movie from him. He LET her steal the movie. This is very very important.)

Remember: Roberts was practically an unknown. She got attention for Mystic Pizza, but … all of the actresses in that film did. It was an ensemble piece. Nobody was ready for Pretty Woman. She didn’t even do a press tour for it. She was making Sleeping with the Enemy. Even her agent wasn’t ready. So there was Gere – a MAJOR sex symbol since the 70s) – playing support staff for a much younger woman – allowing her to shine.

But let’s get back to Gere’s narcissism. I need to clarify what I’m saying.

Narcissistic self-regard is not a flaw in Richard Gere. I am not judging him. I’m not that middle-class. I’m not trying to teach him manners. I am saying that the dynamic he has with himself is interesting and important to explaining his talent and how it expresses itself.

There he was, trapped in a Cinderella story, supposedly the Prince, but he doesn’t give the Princess a helping hand out of the car! Classic Gere! but misplaced in that story, where we are supposed to see him as a “catch”, a prince. The moment is a “tell” and his most honest moment in the film. I love it. We are interesting not because we are perfect. We are interesting because we are flawed.

In Officer and a Gentleman, a love story, his isolation and self-absorption is what made the character so deadly as a boyfriend. The arc of the character is he had to give self-absorption up in order to become a “gentleman”. For almost the entirety of the film we watch him circling only himself, even when he’s with her. It is a fascinating and not quite likable combo.

This is Gere’s sweetest spot: he is fascinating and not quite likable.

He’s so activated, physically and intellectually, in The Hoax, a movie which came and went, but should definitely be accounted for in any serious discussion of Gere’s talent. He was made for a film like The Hoax. It’s perfect. He plays to his strengths: He uses himself consciously, he uses his charm, his good looks, but … he’s up to no good.

Gere needs narcissism as an actor. He doesn’t seem to register as an actor without it. Sex symbols all have a measure of it. They withhold. They are self-consumed. Narcissists drive women crazy. Women want to capture/be captured, be allowed “in there”, be allowed entryway into his precious interior space. Humphrey Bogart was a sex symbol with this kind of thing. Women go NUTS for guys like Zack Mayo in Officer and a Gentleman, and women’s lives are WRECKED in the process. In real life, run from a guy like Zack. He’ll waste your precious time. In the movies, though? As a lead? Gere crushes it.

In American Gigolo, we are given a glimpse of the narcissist “at home”. Gere the actor knows this is a glimpse only the privileged few are allowed to witness. He understands the purpose of the scene: Release the character from his public persona, unfetter him from his “role” and let us see him. Let us see what he does when he’s all alone.

American Gigolo wouldn’t be the same movie without this short Private Moment sequence. The film echoes with loneliness. Julian, sleek and perfect, maneuvers his way through the underworld, trying to maintain his standards (no “rough tricks”, no “fags”), and as he begins to lose control, as his friends abandon him, he faces the abyss at the center of his life and personality. His personality HAS no center. Maybe there’s no “there” there in the first place.

I just want to point out that in the film’s final shot, Gere presses his face up against the clear glass. Earlier, we saw him considering his reflection in the mirror, by himself. At the end, the glass is clear. He can see the person on the other side. They can’t touch. But the barrier is removed.

But in the short earlier scene, where he places ties on shirts, singing to himself, we see behind the mask, and we realize everything else we have seen, every varied role he slips into, is “just a mirage”.

Gere portrays a tailspin of increasing vulnerability over the course of American Gigolo, but nowhere is he more vulnerable and naked than in that two seconds of film when he looks down at the ties, cocks his head lazily, and purses his lips in satisfaction at what he sees.

Wonderful piece, Sheila. You really capture what’s so captivating—yet so impenetrable—about Gere. (Does Affleck have this quality, or is he merely a pretender to the throne?) I’m writing about a narcissist now, so for me this is fun, useful, and timely. Thanks!

the best!