"Sylvia Kristel was a truly remarkable figure in film history." -- Jeremy Richey

Interview with Richey about his book "Sylvia Kristel: From Emmanuelle to Chabrol"

“I was a silent actress: a body. I belonged to dreams – to those who can’t be broken.” — Sylvia Kristel

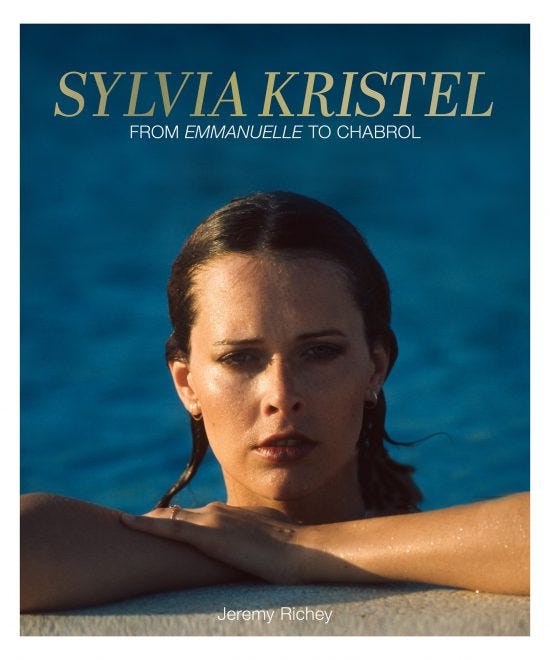

Tomorrow is the birthday of Dutch actress and international phenom, Sylvia Kristel. In 2022 I did an interview with writer/historian Jeremy Richey on his insightful book about Kristel, Sylvia Kristel: From Emmanuelle to Chabrol. I’ll share it here!

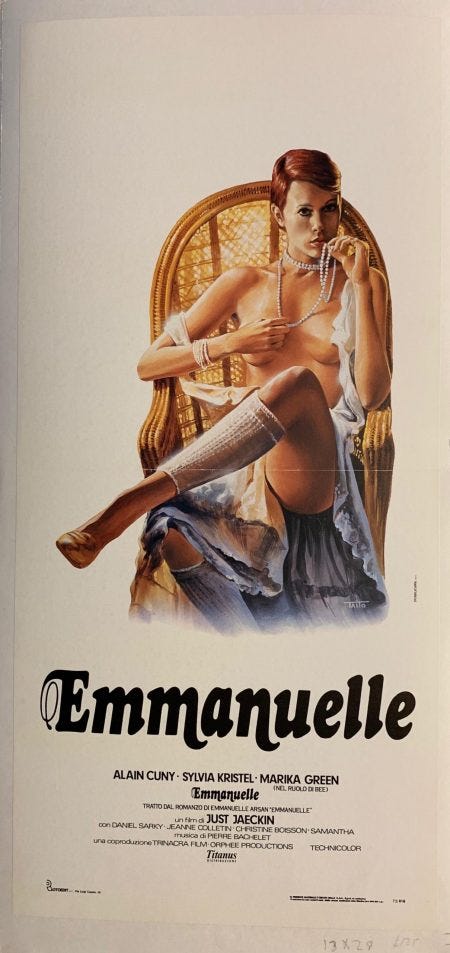

Jeremy Richey’s site Moon in the Gutter was a haven for me for years, as well as an example - when I was just starting out - of the kind of work I wanted to do. While people argued about Marvel movies on Twitter, Jeremy wrote well-researched passionate pieces on Lou Reed, Jean Rollin, or Nastassja Kinski. One of his central interests was Dutch actress and, briefly, international arthouse star, Sylvia Kristel, now known mostly for 1974’s Emmanuelle (directed by Just Jaeckin). The film traveled the world, and saddled Kristel with an unfair “soft-core” reputation. Richey feels there is restorative work to be done in regards to Kristel’s reputation. Camille Paglia agrees, and views Sylvia Kristel as a magical talisman, symbolic of an entire era:

“Emmanuelle absolutely endorses the idea of free female sexuality in that final scene. Sylvia embodies for me the spirit of the sixties and seventies youthquake.”

Richey’s book, published by Cult Epics, shines a light on this young untrained - but instinctive - actress thrust into the international spotlight via the emerging Dutch cinema of the 1970s. She made a splash almost instantly with a small role in Frank and Eva (1973). Other roles followed. When Kristel died in 2012, the obituaries led with Emmanuelle. Richey makes the case, meticulously, for her work’s unique value. Francois Truffaut was a fan, as were Claude Chabrol and Roger Vadim. She turned down some roles which might have been game-changers in terms of public perception (particularly in America where many of her films are - to this day - un-seeable).

Richey scored a couple of interviews with people who knew and worked with Kristel, players in the Dutch cinematic renaissance. He moves chronologically, showing the development of her raw talent. She challenged herself, she took big risks.

Richey’s moments of critical analysis are invaluable:

“Because of the Cats” walks a real tightrope throughout its ninety-eight-minute running time. While its primary function is as a crime thriller, the film also has an evident desire to appeal to a more youthful audience without making fun of them, particularly difficult for the post-1968 film market. Rademakers keeps the film’s portrayal of the young gang as grounded as possible. It never slips into the full-blown caricature it might have in the hands of a less skilled director, with no small amount of the credit going to Claus’ original script as well.

He gets so much done in one small paragraph.

Kristel’s legacy is still close to being consigned to oblivion. There is progress, however. Cult Epics recently put out a box set of Sylvia Kristel’s 1970 films.

Sylvia Kristel: From Emmanuelle to Chabrol is a major work of critical and artistic appreciation and I was so happy to discuss it with Richey.

Sheila O’Malley: Your passions and obsessions run deep and wide. It’s one of the reasons why you are such a compelling writer, and why I was so drawn to your blog, Moon in the Gutter, the moment I discovered it. Having read you all these years, I am familiar with your tastes – the people who matter to you artistically – so I am curious about your desire to choose Sylvia Kristel as the subject of your first book.

Jeremy Richey: I have a great interest in the number of artists I have written about extensively online, like Jean Rollin and Nastassja Kinski, but it was going to always be Sylvia as far as my first full book went. Something otherworldly has been leading me to this since I was a kid first seeing a photograph of her in a Frankfort, Kentucky bookstore in the early eighties. There was something about that photo of her dressed all in black, staring straight into the camera with this unnerving look of confidence, elegance, and sadness. She looked like a poet, and I love poets. Even though I had no way of knowing at the time just how much her work would come to inform my own, I still felt this sort of cosmic connection.

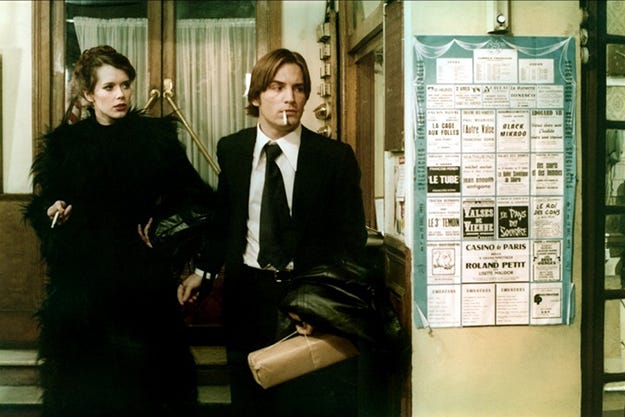

JR: Seeing Sylvia in Walerian Borowczyk’s La Marge in the mid-nineties was the real turning point. I was so blown away and moved by both the film and her performance. Both had a major impact on me like no other and the genesis for the book really came from that moment, which was years before I started writing online. Also, some of it was anger as well as I felt, and feel, that a truly remarkable figure in film history had been all but ignored or written out of it. I wanted to help correct that.

SOM: You use so many primary sources in the book, articles from old Dutch movie magazines and newspapers. I am so curious about how you got your hands on these things. Did you have to get things translated? Was micro-fiche involved? Where do you even begin to start reseaching this?

JR: It was a beast. When I initially started on the book, I was afraid I wouldn’t be able to find enough vintage material and by the end of it, I had literally crashed a computer due to how much I compiled. Key was the indispensable Delpher.nl, which offers more than 100 years worth of Dutch articles from all over The Netherlands. This allowed me the opportunity to access nearly 4,000 relevant articles, interviews, and reviews from Sylvia’s home country, which was an absolute godsend for me and the book.

Plus, I could access material on many of the great Dutch artists that she worked with throughout the early and then late seventies. This really helped flesh out the book, and it was amazing getting to read long-lost interviews with not only Sylvia but people like Rutger Hauer, Renée Soutendijk, Laura Gemser and so many of these great film figures that Sylvia worked with.

Rutger Hauer and Sylvia Kristel filming “Mysteries” in 1978

JR: Making my fortune even greater is the fact that Delpher has their own built in Transcriber and Translator, which is how the Dutch translations began to come about. Of course, I’d always verify on a few different platforms to ensure the translations were as accurate as possible to the meaning and spirit of what was being conveyed.

My publisher, Cult Epics’ Nico B., is Dutch as well and he was able to offer up some vital suggestions and tips for the chapters in the book that cover her Dutch films. Nico was extremely helpful and supportive in general so I will always be heavily grateful and in debt.

While most of the sources came from Dutch and English language materials, I also utilized some harder to access French material since so much of her major work was in France. My French friend Marcelline Block also conducted the lengthy and amazing interview with Francis Lai for the book in French and then translated that for me as well. I believe this was the final major interview Lai ever granted and I think the first time he had ever discussed his work with Sylvia in detail. Such a great honor having him in the book, as well as her directors like Just Jaeckin and Pim de la Parra, not to mention co-stars like Joe Dallesandro and behind-the-scenes players like cinematographer Robert Fraisse, all of whom granted me lengthy interviews amongst a number of other key figures.

Sylvia Kristel and Joe Dallesandro, “La Marge” (1976)

JR: After determining I had a mountain of material to work with, the main trick was figuring out exactly what was important to the story I was telling and what wasn’t. This was an extremely difficult but rewarding process that took months on end. The research honestly never stopped and I am still coming across material, as Sylvia had such a rich life surrounded by other great fascinating artists.

It was important to me to include as much of this vintage material as I could, especially for English language fans who have always been told that she never got good reviews (a total fabrication) and also to show just how many obstacles she faced from a mostly male often hostile press. It was extremely vital for the book that I show the unnecessary obstacles she faced throughout her career, obstacles many of her peers didn’t have to suffer through. Some of the English language articles and reviews from the period are so beyond sexist that it is shocking.

The vintage interviews were so eye-opening, and I felt so grateful to have them to help tell hers and the film’s stories. I’m sure for some readers it will be too much, but I wanted Sylvia’s own voice in the book as much as possible. I already knew that my approach of not being an impartial observer, as well as offering my own critical takes of the films (especially the later American work), would turn off some folks but I just soldiered on with it. This was a very emotional and personal book to write and I hope that comes through for readers.

SOM: You start the book with a very refreshing thought: “I have zero interest in gossip, and I reject the notion that a person’s romantic relationships somehow define their life, especially in the case of a woman coming of age during the sexual revolution”. I have my own pet peeves on this score – I feel like the art is often lost in the so-called salacious details – but I would love to hear your thoughts on it.

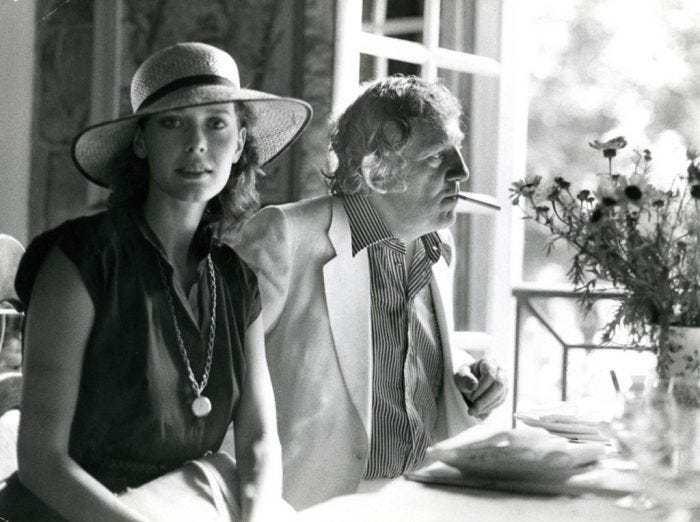

JR: While I hate gossip in general, I’m honestly not sure why I have never had much interest in the type of salacious-driven biographies that so many seem to gravitate towards. I recall as a child being so disturbed by Albert Goldman’s criminal book on Elvis that it still angers me to this day. I was so turned off by the invasiveness of that book and honestly so many other similar hatchet jobs that I read growing up. I don’t care about people’s sex-lives or relationships in general unless they had an obvious impact on the artist’s work, like the relationship Sylvia had with the brilliant writer Hugo Claus. I will probably go to my grave not appreciating how who slept with who offers any understanding to an artist’s life and that applies to anyone I am interested in.

Kristel with Hugo Claus

JR: It’s especially true for someone like Sylvia, whose work has always been viewed in an unfairly sexualized way. The last thing I wanted to do was invade her privacy, so I tried to make sure that the biographical information I gave had some sort of impact on her work. So many just wanted her to be Emmanuelle and that just wasn’t the case at all. Sylvia’s acting, writing, painting and work in general are what interest me, so anyone looking for gossip about her and someone like Ian McShane will come away disappointed and I’m fine with that honestly.

It was necessary to not shy away from the substance abuse issues that plagued her, though, especially in the late seventies and early eighties, as it clearly affected her work and was something she never shied away from discussing. That said, her addiction issues in no way defined her and are very relatable. Who amongst us hasn’t had our own personal issues (I certainly have) with addiction or at the very least hasn’t had a friend or family that has faced similar struggles? The way some people demonize those in the spotlight for issues like this really offends me, and I tried to treat these passages in the book with great care.

Sylvia Kristel and Eric Brown, Private Lessons (1981)

SOM: Kristel’s journey was woven into the rise of Dutch film in the 1970s. I appreciated your exploration of the political/social/artistic revolutions and how they impacted this local film industry. In a small film culture where everyone knows everyone – word got around. Kristel seems to have made a splash almost right away. Was this a “right place right time” thing? Could it have happened in, say, the 80s?

JR: I don’t think so, at least not in the same way.

I write in the book that for me Sylvia absolutely personifies the period that she came of age in, and you can see the hopes of the sixties, the liberation of the seventies to the ultimate disappointment of the eighties in Sylvia’s career like no other. Her career also coincided with both the sexual revolution along with the Feminist movement. I was so happy the day I found the quote by her from the mid-seventies defiantly describing herself as a feminist who believed in equal pay and rights for all women. That was key, as she was ridiculed by so many for Emmanuelle and her general openness towards nudity in film.

JR: Even though I do think her career happened at the ideal moment, Sylvia was far ahead of her time as well, which is one reason that later sex-positive feminists like Camille Paglia were much more accepting in retrospect than some of her peers. It is also super important to remember that Sylvia worked with and was friends with the great feminist Dutch filmmaker Nouchka van Brakel, who was actually a key member of the Dolle Mina (The Netherlands’ most radical feminist organization). It’s also worth noting that nearly every one of Sylvia’s editors throughout the seventies were women, so all of these cultural revolutions of the period powered by women were bubbling under in these seemingly male-made films.

SOM: You write a lot about her physicality, and you connect it to dance. I loved the comparison you made, too, to silent film actresses, and how they had to communicate everything with their bodies. Could you talk a little bit more about this in terms of Sylvia’s approach?

JR: One of the key things to understand about Sylvia and her work is the knowledge that she was an untrained actor, so she operated on a purely instinctual level. This allowed her the opportunity to be completely distinctive. I’m super drawn to actors like this as I often find their work much more alive, arresting and compelling than someone you can sense is falling back on tricks they have learned in acting school.

You can sense throughout Sylvia’s entire career, even in her weaker roles, that her prior experience with dance and movement was pivotal to her work onscreen. For example, if you watch Mysteries, the haunting Dutch film she made with Rutger Hauer on the freezing Isle of Man in 1978, you can see Sylvia utilizing her body much differently than her more trained peers like Hauer or Rita Tushingham. It’s all in her posture and the way she allows (and even invites) the cold to push her entire being forward.

Compare this to the other Dutch film she made with Hauer in the same year, Pastorale 1943, where she holds herself completely another way, playing someone who is trying to exude a quality of confidence. From film to film, we can watch her move entirely differently. It’s super impressive. It’s remarkable how she instinctually understood the importance of physicality, especially in film.

Pastorale 1943

JR: She also had a great natural understanding of how important listening and reacting are to an actor. Despite her lack of training, the level of growth in her skills as an actor grew unbelievably quickly throughout the seventies so much so that it is hard to believe it is the same performer. Anyone not believing me can watch her electrifying and near feral work in her first film Frank and Eva and then compare that to her dignified and somber work in something like Vadim’s Une Femme Fidele which was just a couple of years later.

The noteworthy change is rather jaw-dropping, especially when viewed back-to-back (which critics at the time couldn’t do). Sylvia might have never performed Shakespeare in the Park, but I believe if her career hadn’t been derailed by her time in Hollywood in the late seventies there is no telling just how much nuanced and richer her performances would have become.

It was important to me to draw comparisons to the silent cinema you mentioned, as Sylvia shared so much in common with some of these earliest cinematic trailblazers. Of all of her directors, I think Claude Chabrol understood these qualities the best.

Kristel with Claude Chabrol

JR: So much so that he apparently chucked a lot of the dialogue that was originally in his incredible Alice or the Last Escapade because he understood that Sylvia didn’t need it to communicate. In fact, she could often communicate better with silence than the written word, which was truly incredible. So much so that even Truffaut immediately picked up on it when he sat in with his editor, Claudine Bouché, while she was editing Emmanuelle. It’s easy to see why he considered Sylvia for The Story of Adele H, one of the key early roles she just missed out on that would have dramatically altered her life and career.

Along with Chabrol, Roger Vadim and Just Jaeckin seemed to understand Sylvia the actress the best. She’s so incredibly earthy for Vadim especially. There is a wonderful moment in her first scene of Une Femme Fidele where she trips and nearly falls but continues with the scene. I love that Vadim kept that in. Throughout her career her best directors seemed to understand just how well Sylvia utilized her surroundings. That’s something you can’t fake or be taught.

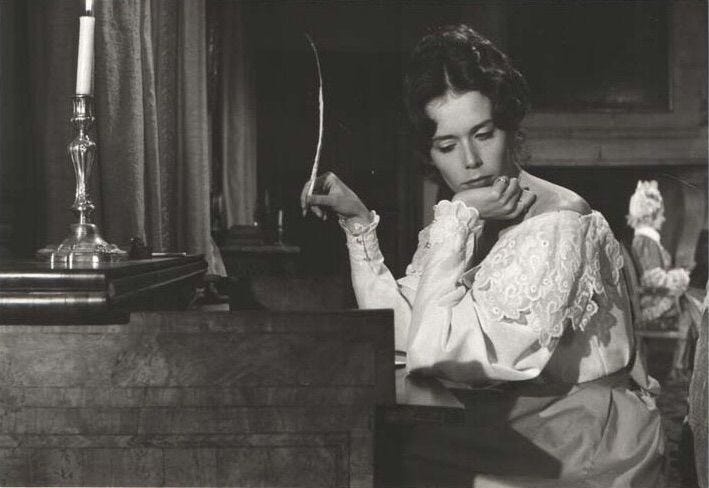

Kristel in “Une Femme Fidele”

JR: That connection to Silent film, and early talkies, is one of the main aspects about Sylvia’s work that draws me in. As her first director Pim de la Parra notes in his interview in my book, Sylvia was a real film scholar. She adored Dietrich and Garbo especially and their influence really shows in her great performances in Alice, La Marge and even Emmanuelle 2 (which feels to me like what a Dietrich/Von Sternberg collaboration would have been like in the seventies).

Photo of Kristel by the great George Hurrell

JR: It’s a shame that Sylvia didn’t get to make the thirties-set Madonna of the Sleeping Cars which, along with Hugo Claus’ adaptation of Madame Bovary, was her great dream project and would have allowed her the opportunity to make a film like Shanghai Express (not silent but still with many of the genre’s defining qualities). It’s also a shame that Sylvia missed out on Herzog’s Nosferatu, yet another role that went to career Doppleganger Isabelle Adjani, as Sylvia would have been perfection. She actually turned down a couple of great films due to her not wanting to work with Klaus Kinski, due to his treatment of women. She was always very upfront about who she did and didn’t want to work with, another aspect of her career that I appreciate.

SOM: There is a moment where you describe the reaction to one of her roles, in Because of the Cats, where she had to play a “blonde bombshell”, and it wasn’t the right fit for her. She loved Brigitte Bardot, but the Bardot “thing” wasn’t her “thing”. How did Sylvia think about her own persona onscreen? Or did she?

JR: Yes, she was often lazily compared to Marilyn Monroe, whom she loved and shared some in common with personally, but they were opposites on screen. Sylvia had a poetic coolness about her so even when she was playing “sexy” it had a more intellectual drive than Monroe’s flirtatious on-screen persona.

The Bardot comparisons made more sense, as they were both European and they had similar career trajectories. In fact, an early chapter in the book details how Sylvia was essentially discovered by Bardot’s partner at the time, Jaccques Charrier, and would end up making one of her great films with Roger Vadim. Despite the differences, Sylvia, of course, didn’t mind these comparisons, as she greatly admired both Monroe and Bardot. I couldn’t say how she felt about her own persona onscreen other than I think she was much more aware of what she was doing than she’s ever been given credit for.

JR: I did want to make sure, as a critic, that I was honest in my approach to each film and performance so I didn’t shy away from pointing out problems with some of the lesser work in the book, like the “blonde bombshell” role you mentioned.

SOM: In a lot of writing about, for example, Elvis, there’s a focus on what-might-have-been, the what-ifs. It’s like 20 years of triumph is erased. We have discussed this before. While I think it’s important to mourn what we have lost, I think it’s also important to turn the focus to what really matters, the work that actually happened. You seem to feel that Sylvia Kristel is long overdue for a serious re-evaluation – or maybe even just a proper evaluation, period. Your book feels like an act of redress, and I wondered if you had any thoughts on that.

JR: I did absolutely mean it as an act of redress, so thank you.

As much as I regret that she passed on opportunities to work with directors like Ingmar Bergman and Maurice Pialat, which I detail towards the end of the book, I want the proper focus to be on the great work she did. Like Elvis, her story is part tragic but mostly triumph. It’s a bummer that works like Une Femme Fidele, La Marge and Alice have yet to get their due, but they will. Great art survives and Sylvia made a lot of it, throughout a number of fields.

So, while I think it’s okay to look at missed roles in everything from King Kong to Body Heat to Once Upon a Time in America as regrettable, ultimately the great films she made make up for those. Ironically, Sylvia’s dismissal of several plum parts helped give rise to both Adjani and Isabelle Huppert.

Speaking of Huppert, probably the great role that I would have most liked to have seen Sylvia in was in Pialat’s masterful LouLou. It would have given Sylvia another opportunity to work again with the great Gerard Depardieu (who she had held her own with in the marvelous Rene the Cane) and I think would have completely reshaped her career for the eighties.

Kristel and Depardieu, “Rene the Cane”

JR: Pialat was very vocal at the time about how disappointed he was and even had Huppert and Depardieu watching Sylvia onscreen in the film, so in a way he got her in his film anyway. Funnily enough, he had also put her image in his earlier Passe ton bac d’abord. Pialat was just one of a number of truly masterful filmmakers inspired by Sylvia, who sadly never got to work with her. Polanski was another, and of course Bergman. I look upon these missed opportunities as just adding to the richness of her story, although looking at the films she could have made in the eighties if she hadn’t mistakenly come to America and became saddled with such outfits as Cannon does leave a lump in my throat.

SOM: If someone has no idea who Sylvia Kristel was, and wants to see her in action, where would you suggest they start and why? What role captures her best?

JR: Sadly, for the most part her greatest performances in Une Femme Fidele, La Marge, Rene the Cane and Alice are currently missing in action officially. Even more regrettable is the fact that her great films that have been released on disc, like the first two Emmanuelle films, and her Dutch work (released by my publisher Cult Epics) are not streaming as of yet which sadly means that the films that are streaming here are mostly amongst her worst. Frustrating, but I know that will change.

Ignoring all that, her work in both La Marge and Alice are the ideal entry points. I highly recommend the recently released Sylvia Kristel 1970’s Collection from Cult Epics as it allows viewers not only the opportunity to see two of her finest Dutch films (Mysteries and Pastorale 1943) but also her brief turn in Playing With Fire for another one of her great directors, Alain Robbe-Grillet.

People who have always considered Sylvia as just the erotic star of works like Emmanuelle or Private Lessons have the story wrong. Sylvia Kristel was amongst the greatest and final figures of the much-missed European Art House of the sixties and seventies. That’s the main story my book tells. It’s a celebration of an extremely smart and talented artist and a period in art and popular culture that was unlike any other.

You can purchase Richey’s book at Cult Epics.

I recently watched Julia starring Sylvia Kristel, and I was surprised by how captivating the film is. The storytelling, emotional depth, and Kristel’s performance are exceptional. Here’s the link ( https://youtu.be/giSNOpMLFhI?si=VlE7FuB6JUIDg1Xm ) where I found the movie.

Why is such a great movie so underrated and rarely mentioned in discussions about Sylvia Kristel’s work? It feels like Julia deserves much more attention alongside her iconic roles like Emmanuelle. Does anyone else feel the same? Would love to hear your thoughts!