Outside-Inside: John Cassavetes' "Minnie and Moskowitz"

Where is Charles Boyer when you need him?

Me myself with my face pressed

Up against love's glass…— Indigo Girls, “Love Will Come to You'‘

Minnie and Moskowitz is what a romantic comedy looks like when it’s directed by John Cassavetes. Fear of loneliness is the unacknowledged engine driving romantic comedies. Why else do rom-com couples act so wacky, chasing each other with butterfly nets, or commandeering Coast Guard boats to chase down yachts, or sneak around spying on each other? Loneliness is so excruciating people will do anything - anything - not to feel it. Loneliness shimmers on the outside of your skin. And because other people are so fearful of catching it, they back away, isolating the lonely even more.

The people in John Cassavetes’ films live with loneliness not just licking at their heels, but screaming in their ears. In reaction, his characters do not retreat into themselves. They do not feel sorry for themselves. They don’t decide to pull themselves up by their boot straps, or if they do, they end up getting too drunk. They don’t give themselves time to dwell on their interior worlds. They avoid solitude and contemplation, they avoid silence. To avoid silence, they stay up all night, they dance and flail around, they goof off, get drunk, and then - more often than not - they crack up suddenly in the middle of the next day. Cassavetes’ films are known for their emotional honesty. Sure. But this is sometimes characterized - or mis-characterized - in the modern therapeutic sense. People feeling things, letting it all hang out … it’s healthy, right? Sure, okay. But if you want to have a grounded honest conversation about feelings, just try it with the characters in Faces. Or Husbands.

Sit down at the dinner table with the construction guys in A Woman Under the Influence and open up about your feelings. See how well it goes over. Mabel would crack a joke and blow a raspberry off to the side. The characters in Faces can’t slow down. When they do, they come to a crashing halt.

A romantic comedy emanating from fear of silence is my kind of romantic comedy.

I watch Minnie and Moskowitz, and I think, “These two crackpots have as much of a shot of ‘making it’ as any conventional rom-com couple.” MORE of a shot, probably, since they are at least aware of the void, aware of what’s beyond the charmed circle.

The final scene of Minnie and Moskowitz always takes me by surprise, and I’ve probably seen the film 15, 20 times. Suddenly, with seemingly no warning, the film moves to a scene of inclusion, a scene taking place inside the charmed circle of warmth.

Being “outside” the circle is the dilemma of Cassavetes’ characters, whether it’s Mabel in A Woman Under the Influence, or Nick in A Woman Under the Influence (he’s as much of an outsider as she is), or Sarah in Love Streams, all of the characters in Faces. Every single character longs to get “inside”. Their faces pressed up against love’s glass. So they drink, they dance, they laugh, they go bowling, they visit a medium, they buy an entire menagerie and bring it home in a monsoon, all in the hopes that their behavior will say to the world, “Hey, look how inside the circle I am! I am SO OKAY with everything, see?” Maybe the Behavior will change how they Feel. It’s Outside-In logic: If I laugh louder than everyone else, maybe it will look like my laugh is real, maybe it will look like I really feel the things I so wish I could feel. Maybe having one more drink will do it, maybe one more drink will bring "the click”, as the tragic Brick in Cat on a Hot Tin Roof calls it. The moment Cassavetes’ characters stop laughing, drinking, dancing, the isolation roars back.

Minnie and Moskowitz is seen as Cassavetes-light, I suppose. I am 83% certain it’s the first Cassavetes film I saw. It was so long ago, and I didn’t really know who any of these people were. I had a lot to learn. I was 17 or 18, and already studying acting, I was engrossed in people like James Dean, Marlon Brando, Natalie Wood, Al Pacino, seeking out all “the great performances”. My self-directed program of education. But I had no context (yet) for Minnie and Moskowitz. The film made me so damn SAD, and yet there were so many wacky shenanigans, I couldn’t grasp the tone. (I was too young. To me now, at this age, it practically feels like a documentary.) But as a teenager, I did understand the film was a journey of finding “belonging”. I had friends. But there was always uneasiness in my head, wordless fears and anxieties (I now know I had a major mental illness and it wouldn’t get clocked for years, so I chalk a lot of this general uneasiness/dread to some inner biological knowledge: I knew). Sometimes - when it got really bad - I dreaded the future. Where did this dread come from? It felt like it came from outside of me. I was an ambitious kid. I already knew what I wanted to do. It was a passion. Maybe I knew somewhere how hard it all would be. I yearned for love, I yearned for romance, I so wanted to find a mate, not a husband necessarily, but a mate, I wanted to be “picked”, but more: I wanted to be SEEN. I was “seen” as an actress, I was “seen” by my friends. But, to put it bluntly, I wanted love. I was a romantic with nowhere to put it. I traveled a lot of hard road. The worst was being lonely while I was in a relationship. I’d rather be alone, thank you.

From the same Indigo Girls I opened with, the final verse:

And I wish her insight to battle love's blindness

Strength from the milk of human kindness

A safe place for all the pieces that scattered

Learn to pretend there's more than love that matters

Good luck.

Cassavetes’ films gave me a glimpse - early - of what it all might mean. This Substack should be called The Loneliness Chronicles, but honestly, I’m not lonely anymore. I have a rich life, with nieces, nephews, friends, work I love, things to look forward to, friends from every stage, grade school to adulthood. I don’t feel outside anymore. But I struggled, mightily, as a teenager, a 20something, and let’s not even discuss the 30something years. One could not characterize my response to Cassavetes’ films in a cozy way, with canned phrases like, “I feel validated by the films” or “I feel SEEN by the films”. Nothing so domestic, nothing so manageable.

In A Woman Under the Influence, Mabel (Rowlands) returns home from the asylum after a six month stay. She tucks her three children into bed, all as her husband Nick (Peter Falk) looks on at the doorway. The exhausted couple start down the stairs. She walks in front of him, and suddenly says, in a totally conversational tone, not responding to anything he said, “I am absolutely nuts!!” She sounds surprised, as though the reality is really just occurring to her. Falk murmurs, “Tell me about it.” She continues, almost in a tone of wonder: “I don’t even know how it all got started!”

Now this is emotional honesty. How did all of this even get started? What the hell HAPPENED? (See: my 30s.)

My friend Michael and I bonded in our love for these films. We felt like we were members of a secret club. By then, I was in my 20s, fully versed in Cassavetes’ influence on filmmaking and his place in American independent cinema. I was out in the world. I knew all the films. I caught them in repertory when I could. What I valued by then was the inspiration Cassavetes - and his merry band of collaborators - provided: of living communally, of creating things with your friends, of divesting from commercial concerns, of making personal work. What mattered to Michael and me … what pushed us - was Cassavetes’ example, so crucial in a bottom-line-driven profession: do it your own way, maintain your values, don’t sell out, surround yourself with like-minded artists, don’t get bitter. Make your work. Make it your own way. Don’t compromise.

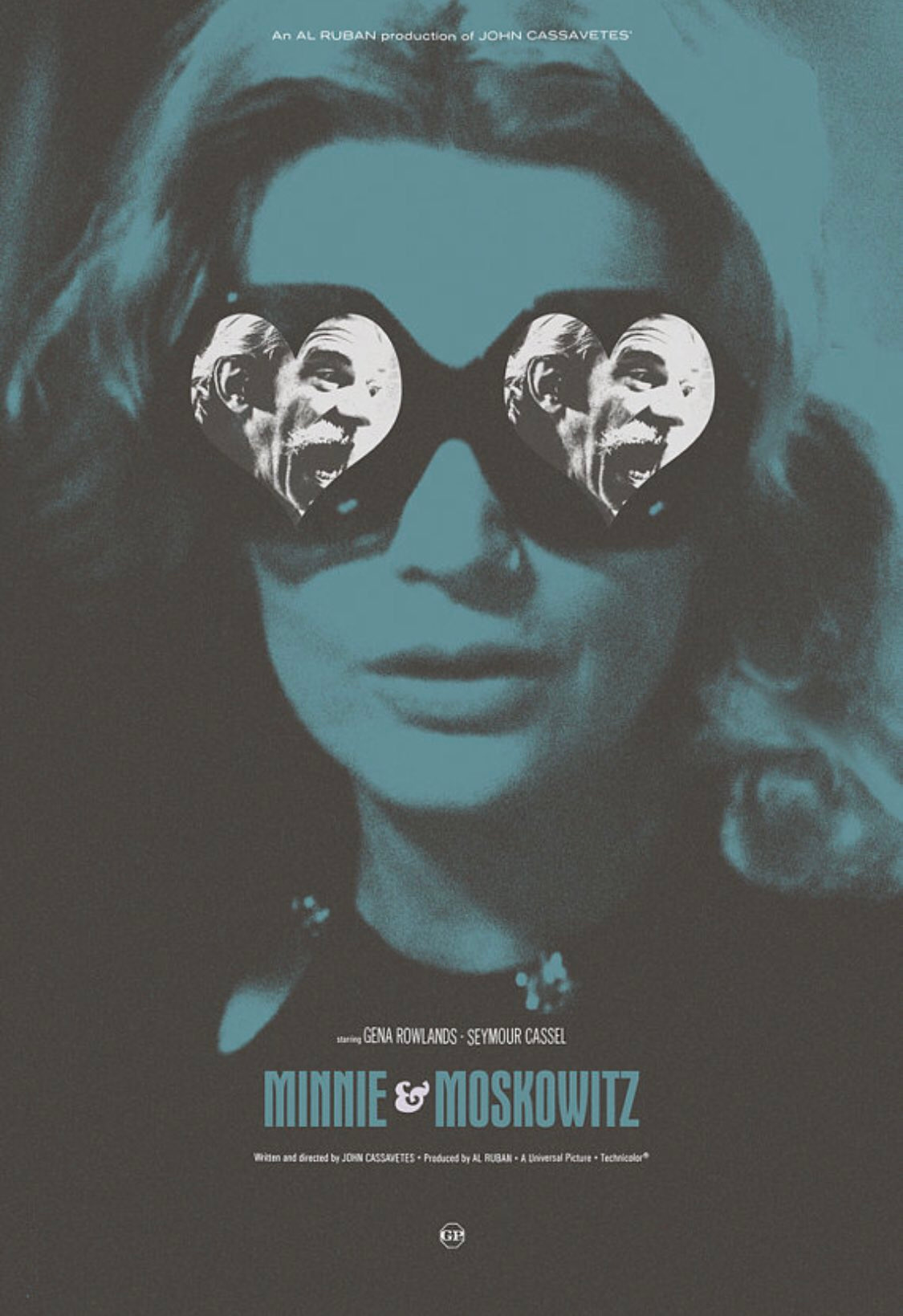

Like most romantic comedies, Minnie and Moskowitz presents the coming together of two unlikely people – Moskowitz (Seymour Cassel), the loud-mouthed kind-hearted but completely unpredictable parking attendant, and Minnie (Gena Rowlands), the high-class woman working in an art museum, wearing the mask of put-together respectability. Looking at her blonde helmet of hair, her massive sunglasses, you’d never know this woman lives with loneliness as a permanent condition. She doesn’t know how to “be herself” (a common theme in Rowlands’ performances).

The problem is exacerbated by Minnie’s beauty. It’s a unique problem, and perhaps we wish we could have such a problem. But Rowlands provides us with the opportunity to 1. acknowledge her beauty and 2. acknowledge the isolation of being that beautiful and 3. get insight into how … weird it must be, to be that visibly beautiful. Minnie and Moskowitz confronts Rowlands’ beauty and glamour head-on. Men look at Minnie and are in awe of her, and they break her down into her parts, almost automatically: “Your skin is so soft.” “You have a terrific body.” She’s not a person to them. She’s not even whole. Minnie doesn’t seem to resent this. It doesn’t even look like she knows what is being done to her, but she does know something is wrong.

In her first scene, she sits at the house of a colleague, drinking cheap wine, getting totally trashed. She rambles a long monologue about how much she loves the movies, but she feels like the movies “are a conspiracy”, they “set you up”. Her drunkenness is palpable. “I’ve never met a Charles Boyer!” she slurs, her voice high and irritated. Where is Charles Boyer? Why isn’t the world filled with Charles Boyers running around? The movies are a RACKET. When Minnie leaves, and heads to the cab waiting outside, she wipes out and falls down the stairs (Nobody – and I mean nobody – plays drunk like Gena Rowlands).

This is our introduction to Minnie, and it’s a brilliant choice. She’s wasted and vulnerable and chatty. She lets us in. If we didn’t get this glimpse, we would never know. Mostly, her mask is firmly in place. She’s gorgeous. She’s got it together. But we’ve seen underneath. The movies “set you up to believe in … everything”, she says, sounding like a hurt teenage girl.

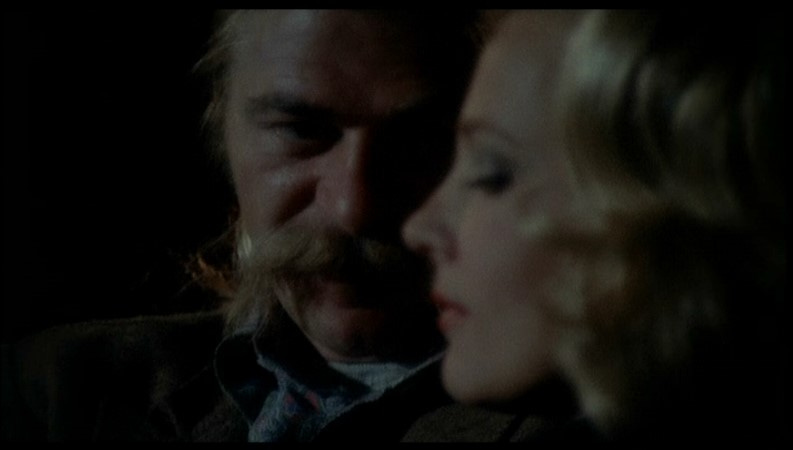

In Cassavetes-land, Charles Boyer, the quintessential cosmopolitan European lover, shows up in the form of the mustached-ponytailed Moskowitz, not exactly a fair trade. At first. Minnie and Moskowitz’s romance does not unfold in any way recognizable in terms of cinematic or literary cliches. Time stretches out. When they jointly tell their mothers they have known each other for “four days”, they both get surprised. “Four days? Has it only been four days??”

Love can be like that.

Someone like Minnie needs to feel safe. People have hostile reactions to beautiful women who dare to “need” something. But let’s not lie to ourselves or sugarcoat. Minnie is a handful. She can’t say what she needs out loud. She doesn’t know how to be herself, because what does “be herself” even mean? Maybe, though, being alone isn’t the worst thing. In the first scene, she asks gentle questions of her friend - who is older than Minnie. Minnie wonders if there is ever a point in your life when you give it up, the sex thing, in other words, the love thing, in other words: do you ever stop hoping?

In the last scene, the music suddenly starts, sweet and friendly and whimsical, and the kids run around the lawn, and people blow up balloons, and the mothers-in-law commiserate, and people dance on the picnic table, and Minnie sits there, wearing gigantic pink sunglasses and a long white veil, and she’s laughing, really laughing …

Minnie and Moskowitz are a crazy couple and they’ve married each other after a chaotic four days, and the whole thing is unconventional as well as a long shot, but what matters is the experience she has for the very first time, sitting there on the lawn in the sunshine. It is an experience that, of course, has to do with him, but not only with him.

She’s sitting outside but she’s inside at last.

This is a re-vamping of a very old post on my site. I’ll resurrect these here occasionally.

Looks like I'm gonna be the first one to jump into the pool.

Thanks again, Sheila, for another tasty post on one of my favorite Cassavetes movies. You hit all the notes, making me smile. I'm also happy you made mention of the rich life you enjoy today.

Wishing you more joy and love.

I would only add, the scene between Seymour and Tim Carey at the top of the movie gets me every friggin' time. It's so good watching them go back and forth. I gotta pop it in:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jTFJLyUYxiA

So, so good. LOVE that you can hear Cassavetes laugh in the background at the end of Morgan Morgan, waitress scene.

Aw, that was swell.

Jimmy

Sheila--

Was just reading one of your fantastic Ebert columns on Gena Rowlands--in which you wish that more of what she and Cassavetes brought to film was in film today. I wrote my film MARIANNE--Isabelle Huppert's first one-woman film--for Rowlands. Rowlands turned it down, I think because she was 85 at the time...but I wrote it for her because MARIANNE is 100 percent about the Cassavetes ethos, in a way no film has ever dared try. (I urge you to read what Carlos Valladares says about it on Lettrboxed--he calls it "a seminal film of the 2020s.") Coming to my point: ebert.com won't review it. I've written you about reviewing it, too. It's been completely ignored by every legacy critic--I've tried them all. The film cannot find a lick of distribution--essentially, it doesn't exist. My point: like you, I

wish more of what Gena and John brought to film was in film now. I've done something substantial to change that...result, crickets. It almost feels like blacklisting. Sorry to write you here, but at least I know you will read what I've written here...and perhaps, get involved. The amount of respect I have for you cannot be measured....Michael Rozek