"I think I made you up inside my head."

On Lili Horvát's gorgeous Preparations to Be Together for an Unknown Period of Time

Lili Horvát's Preparations to Be Together for an Unknown Period of Time (2020) opens with an epigraph, the final verse of Sylvia Plath's poem "Mad Girl's Love Song":

I should have loved a thunderbird instead;

At least when spring comes they roar back again.

I shut my eyes and all the world drops dead.

(I think I made you up inside my head.)

It's the perfect set-up, and a striking choice to this Plath-fan. More on the poem, and its connections to the film's themes, in a bit.

I read a review of Preparations, written by a male critic, who waxed rhapsodic about how the "female gaze" of the director meant the lead character was not "pathologized" as she might have been otherwise, and so ultimately the film was about the character's "resilience", not her suffering. I won't say he doesn't have a point, he absolutely has a point, but this particular tone and attitude is so common it feels like a stifling propaganda push. It's irritating when men proclaim what is/is not "healthy" representation of women onscreen, and it's equally irritating the assumption that suffering = "pathology". As a woman who has sometimes suffered - at length - I take issue with this characterization. Women are, after all, humans, which means sometimes we fall apart, particularly when we're in love. Love, especially thwarted love, doesn't tend to encourage resilient sane behavior. This is not news. In As You Like It, the cross-dressing Rosalind, a Ph.D. candidate in Love, declares,

Love is merely a madness; and, I tell you, deserves as well a dark house and a whip as madmen do; and the reason why they are not so punish'd and cured is that the lunacy is so ordinary that the whippers are in love too.

If only Rosalind knew she didn't NEED a man to be happy! Poor retro Rosalind. Never mind how she swashbuckles her way through the forest, taking charge, plotting and scheming and - ultimately - helping everyone (including herself) find their bliss, no matter the subterfuge and the costumes they have to wear to achieve it.

Notice how Rosalind softens the severity of "madness" with the diminutive "merely". It's "merely madness", don't worry about it. You're falling in love, i.e. you're losing your mind, it's perfectly normal. Welcome to the club.

Preparations is a dreamy somnambulistic portrait of longing, longing ignited by protracted loneliness, so protracted that the world has turned into a mirror, a warped mirror, or maybe it's a fluid watery mirror filled with shadows, sparked with light, interrupted by ripples. Maybe you get a glimpse of the bottom, but maybe not, maybe the water is too murky to see through. Reality itself seems to shift. The whole movie takes place in an altered state of mind, a woman jolted into new awareness - sometimes painful, sometimes piercingly sweet - where nothing is what it seems. She doesn't trust her perceptions. She knows she's entered an in-between place, where all is in flux. She can't hold on because there's nothing to hold onto.

The canon of films about loneliness - real loneliness - is small because loneliness is a societal no-no. You are maybe allowed a season of loneliness but you must come out of it and join the social world again. Being lonely permanently is forbidden. Lonely people are embarrassing. I wrote about this in my piece for Film Comment on Tom Noonan's What Happened Was ..., those trailing ellipses evoking the abyss in which the two characters (played by Noonan and Karen Sillas) live. Babies fail to thrive when they are not hugged and cuddled and loved. Can't the same be true of adults? The pandemic brought loneliness to the forefront in a new and urgent way. It was even referred to as a "public health crisis". Good. It is. Let's talk about it.

Tom Noonan and Karen Sillas, What Happened Was …

At a certain point, extended longing for a partner - imaginary or potential or otherwise - transforms into pining. Longing can be endured and/or re-directed. Pining is harder. Longing is specific. Pining is general. You can't just pine for something in one area. You end up pining for everything. This is where the uber-rational scientist Márta Vizy (Natasa Stork) finds herself in in Preparations to Be Together for an Unknown Period of Time.

40-year-old Márta, a successful neurosurgeon at the top of her field, with no husband, life partner, or extended family, moves back to Budapest after twenty years in the United States. She never thought she would return, but after a passionate one-night hookup with fellow Hungarian neurosurgeon János Drexler (Viktor Bodó) at a conference in New Jersey, she pulls up stakes. The two made a date to meet at a certain time on a certain bridge in Budapest a couple months later. (Clearly, they both were familiar with Richard Linklater's Before Sunrise.) Márta keeps the date. It's already a dramatic situation, but Márta makes it even more dramatic. She doesn't just take a trip home. She vanishes from her life in America without giving friends or colleagues a heads up. She waits on the bridge at the agreed-upon time. Drexler is a no-show. The intensity of Márta’s disappointment is heartbreaking.

Desperate, unable to let it go, she tries to find him at the hospital where she knows he works, and catches a glimpse of him on the sidewalk. She confronts him. He is confused and alarmed at this woman demanding to know why he didn't show up when he said he would. It is obvious: he has no idea who she is. She must have mistaken him for someone else. Disoriented and devastated, Márta collapses on the sidewalk, attracting a concerned crowd of strangers.

All of this in the first ten minutes. Preparations to Be Together for an Unknown Period of Time takes place in an urban looking-glass world, where yearning for a companion is so acute it takes on corporeal form, the fantasy partner beckoning her across the bridge, forever out of reach. Márta is a practical woman, and her specialty is the human brain. The brain is an organ: she can operate on it if necessary. But there's something elusive, still, something an operating table can’t reveal. At one point, she sums up her life: she has one ex-boyfriend, two good friends, and no family. Bare bones already, and more bare post-Drexler. All she sees and needs is him. Their encounter (even if she made it up) awakens her and she cannot get back to her former self. She can't wax philosophical, she cannot say breezily, "People come into your life for a reason, a season, or a lifetime." "Reason" and "season" will not do. Drexler is there for a "lifetime". He has to be. How had she ignored her loneliness? She's been asleep for years.

Horvát peppers the action with scenes between Márta and a psychiatrist (Péter Tóth). These are placed outside of time and space. It's not clear when they occur, if they are the same session, or a series. The way Márta speaks is "mad", disconnected from reality, but her eyes shine with certainty. These scenes are a device, providing an entryway into Márta’s state of mind. They force Márta to verbalize the wordlessness. Horvát sidesteps realism: Marta's ice-blue eyes match the blue wall behind her: her face fills the screen. (Cinematographer Róbert Maly does superb work throughout.)

There are signs and signifiers afoot as Márta wanders the streets of Budapest, through spaces that are often eerily empty: stairways, sidewalks, libraries, an unpopulated city. The glimpses of potential meaning could help Márta make sense of what is happening, but they operate through dream-logic. Life, however, must go on.

She gets a job at a hospital, where the administrator is curious as to why this accomplished ex-pat would want to take such a pay cut and reduction in status. He warns her that the staff might hold her high reputation against her. All of this comes to pass. In staff meetings, Márta's contributions are often greeted with hostile silence. Who does she think she is? seethes through the air. The hospital is over-crowded and under-staffed. Innovation is not encouraged. One case intrigues her: a son brings his father in for diagnosis. Márta has some suspicion of what is wrong, but it requires her to go against the engrained wisdom of her colleagues. Márta finds an unlikely ally in the man's son, a twentysomething medical student named Alex (Benett Vilmányi), who at first seems hostile, until Márta realizes his hostility may just be attraction. She can't tell. She doesn't trust her impressions anymore.

Life takes on a darkly magical quality: when Márta comes to after collapsing on the sidewalk, one of the first faces she sees is Alex's, a boy she hadn't even met yet. And now here he is again, in her office. Is he the one she was supposed to meet? Was Drexler placed in her life to lead her to Alex? Look out. This way danger lies.

Horvát's filmmaking is so compelling, so confident and insistent, Preparations to Be Together for an Unknown Period of Time pulls you into its specific rules of engagement, similar to what Krzysztof Kieślowski does with The Double Life of Veronique. The two films are interested in urban spaces, and the very specific loneliness of living in a city. The films evoke the feeling one gets - usually when the day melts into twilight - that someone is "out there", your other half, your perfect partner, your missing piece, or maybe it’s your double, the alternate you ... You feel this absence like a phantom limb, so vividly you could almost reach out and touch it. There is a person-sized shape walking along beside you. Both films are ghost stories in this way.

In an interview with The Movable Fest, Horvát spoke about how she and Maly were inspired by the photographs of Saul Leiter, when first discussing the look and feel they wanted. Horvát recounts:

The first photo I saw made by him was via an exhibition. It was a taxi in New York, made in the ‘50s or ‘60s, [where] we look from outside and we see the backseat and the arm of a man grabbing that handle, but this is all we can see of the man, this arm.

Saul Leiter, Taxi, New York, 1957

Horvát goes on:

I called Róbert right away and said, “Oh, I found the way we should show Janos Drexler, this is the way.” Then we started to explore Leiter’s work further, and it is to Róbert Maly’s credit that he achieved a way to [capture this feeling] in the moving images as well.

There are multiple scenes where Márta jumps in a cab to follow Drexler, her behavior tipping over into stalking. She seems capable of anything. The city, as seen through the windows of the cab, are blurred out, like watercolors, the streetlights and neon bleeding into the darkness, as the two cars hurtle through the streets. Mirrors are a motif throughout, and in the taxi, the taxi driver's face is seen in the rear view, the driver glancing back at Marta, perceiving all, as taxi drivers do. (It’s a benign version of Travis Bickle’s eyes.)

Drexler is glimpsed only partially, the back of his head, his glancing profile, pieces of him beckoning Márta on, as she tries to get close enough to …. what? Understand him? Confirm he is real? She spends time looking up photographs online of the New Jersey conference where they met. She finds pictures of the two of them in the crowd, confirming at least that they both were there. She comes across one photo where the two of them sit in the same row at a lecture, Drexler staring ahead, and Marta staring down the row at him. It looks photoshopped though. It can’t be real, right?

All of this connects to the Plath poem at the start. Both film and poem present a woman madly in love with a man she may very well have made up in her head. It's not quite as dire-scary as Shirley Jackson's "daemon lover" but it's close. There is something a little bit uncanny going on.

And now a couple of observations about Plath’s poem:

Plath wrote "Mad Girl's Love Song" in 1953 while a student at Smith College. 1953 was a crucial year for Plath. A crucible year. She won a coveted spot in the guest editor program at Madamoiselle magazine, and spent a month living and working in New York City (the hallucinatory experience of which eventually made up the bulk of her novel The Bell Jar). 1953 was also the year of her first suicide attempt. "Mad Girl's Love Song" was printed in Madamoiselle. Plath was extremely proud of the poem, mentioning it in letters to her mother, her journal, etc., calling it the best thing she had ever done. It’s a villanelle, one of the most punishingly rigid forms in poetry (Plath went through a big villanelle phase; I suppose most poets do), and is listed under the "Juvenilia" heading in the collected volume of her work (edited by her estranged husband Ted Hughes, a controversial choice if ever there was one). Plath's final burst of creativity took place a decade later in the fall of 1962, the season her marriage deteriorated. Poems poured out of her at white-hot speed, alarming her loved ones, terrifying now-famous poems like "Lady Lazarus", "Daddy", "Fever 103", the bee poems, "Tulips", and on and on and on and on, all emerged in a 4-month period, at a rate of sometimes three a day. She declared to her mother, "These poems will make my name". She was right, although she wouldn't live to see it happen.

Compared to the pitiless unblinking sweep of Plath's later poems, "Mad Girl's Love Song" is a self-conscious squeak. It has the show-off-y energy common in Plath's early work, sweated over as an ambitious teenager. (Ted Hughes remembers her writing poems with a Thesaurus balanced on her knee. It shows.) Plath was hemmed in on both sides by opposing pressures:

Prepare for a dazzling career, be brilliant academically.

Be marriageable (i.e. virginal), prepare for domestic life and spending your life cooking and cleaning and mothering.

It was explicit and implicit: If you are a woman, you cannot have both. The electrifying tension between these incompatible demands is the detonator for Plath's work. She was fully aware of the pressures on her. She knew exactly what was going on. Janet Malcolm calls The Bell Jar "an indictment of the fifties" and indeed it is.

Plath wrote so many poems about madness and obsession, jealousy and grief, sexual passion, and all the rest. Her mature work obliterates the juvenilia. And yet Horvát chose to feature the "juvenile" poem. This fascinates me, and inspired the following riff as I thought it out.

Something in Márta’s behavior, her impulsive choices, her reckless abandonment ... feels adolescent. This is not a criticism of Márta or a judgment. This is what can happen when love is thwarted. Arrested development. You haven't exercised grown-up muscles, muscles of perspective, proportion, philosophy. You are swept away by a crush. Everything rides on a one-night stand. Márta can't stop the flood. She succumbs. She is an adult, with a major job - she literally touches other people's brains - but in the love realm, she's Rosalind, cavorting carelessly through the urban forest, chasing a bliss that may very well be delusion on her part. Or maybe she’s Orlando, too, Rosalind's love object, who loves a woman but messes it up through adolescent bumbling. Orlando is also strangely attracted to the bossy boy who's taken him under his/her wing. Rosalind acts in ways counter to her own fulfillment, and it's tragic for her. She's preparing a man to love properly, yes, but the tragedy is she might be preparing him for another woman. Cue: moaning and writhing and aching and burning. I’m using the word “preparing” deliberately. The film’s title is so key!

Preparations’ blurry-liquidy city-night imagery can be found in Plath's villanelle:

The stars go waltzing out in blue and red,

And arbitrary blackness gallops in:

I shut my eyes and all the world drops dead.

Drexler isn't just a guy Márta hooked up with. She’s gone crazy with desire for more more more. Plath's lover sends her into a similar frenzy:

I dreamed that you bewitched me into bed

And sung me moon-struck, kissed me quite insane.

(I think I made you up inside my head.)

Márta is "sung moon-struck" and for sure “kissed quite insane”. (Go, Drexler!) She left America without telling anyone. She rents an apartment, a dump, really, but she can see the fateful bridge out the window. She wants to stay close to the dream.

She puts a mattress on the floor, and invests in no other furnishings. Her life empties out. She and Drexler connect again, tentatively, as colleagues, and as ... something more, maybe, and Márta’s hunger for the dream quiets down, or at least she is able to contain it. She knows she freaked him out. Maybe if she stays very very still, he won't be afraid to come close. Maybe she manifested him. He still doesn't remember New Jersey (or does he?), but he finds himself drawn to her, this woman on the periphery of his life, this woman with the intense hurt blue eyes.

There's a marvelous sequence where Drexler stands outside her apartment, waiting for her. The two stand across the street from one another, staring wordlessly.

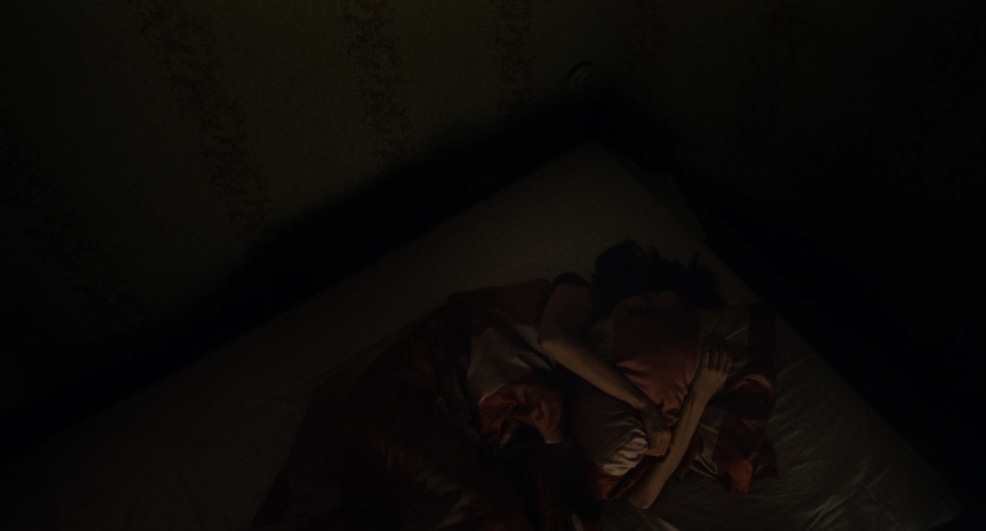

Never taking their eyes off each other, they start to walk in the same direction. They keep pace with one another, but never cross the street to continue on side by side. It's the actors' mirror exercise. The mirror isn't on the wall, it's life itself. They walk for hours this way, until Drexler seemingly vanishes into thin air. Márta lies on her mattress, curled up, or splayed out, staring at the ceiling, pining desperately.

The apartment is shot in a way where its dimensions and layout are barely comprehensible: it seems to change every time you look at it. Where is the kitchen again? Where is the front door? Marta barely seems to know. Possessions would jolt her out of the dreamspace into reality. There's another Saul Leiter photo called "Sleep", and it’s different from his exterior shots, all those cabs and telephone booths and signs and sunlit sidewalks.

Saul Leiter, Sleep, 1970

The woman is abandoned in sleep, her arm flung over her head. She's oblivious to the creepily voyeuristic camera. The mirror hanging on the wall opens up the room beyond, a glimpse of another world. A chair. A bare wall. As sparsely furnished as Márta’s apartment. So many of the shots of Marta in bed, sleeping, evoke “Sleep”.

Tom Noonan’s What Happened Was… came to mind a lot. The film opens with an overhead shot of Jackie (Karen Sillas), sprawled out in bed, ferociously lost to the world, an intensely private moment.

Karen Sillas in What Happened Was…

What distinguishes Preparations, and it's there in What Happened Was... as well, is its freedom in the telling. The normal constrictions do not apply. There's humor present, believe it or not, the humor of finding yourself in such an embarrassing emotional situation, being so completely undone, and the crazy shit you get up to when you have had it with being alone. The mood is not unremittingly grim. On the contrary, the experience of life is so heightened, that the longing - although painful - is almost pleasurable. Márta wouldn't go back if she could. It's hard to picture Márta and Drexler settling down into the everyday world of sharing dinner and the TV remote, giving a goodbye peck on the cheek before heading out to work. Not possible. Love is a FEVER, and it BURNS YOU UP FROM WITHIN. Sylvia Plath and Preparations wouldn't have it any other way.

It becomes clear that the title means what it says. The film is prologue, the film is "preparation". Something else will follow. The "something" is "unknown", but it's there in all the mirrors, in the dizzying glimpses of the city reflected in the river, a drowned Atlantis, it's there in Marta's empty apartment, the emptiness charged with the anticipation of being filled. Preparations knows pining is terrible, but longing reminds you you’re still alive.

Saul Leiter once said,

There are the things that are out in the open, and there are the things that are hidden, and life has more to do, the real world has more to do with what is hidden.

Preparations to Be Together for an Unknown Period of Time "has more to do with what is hidden". And there's nothing more real than that.

Preparations to Be Together for an Unknown Period of Time is currently streaming on the Criterion Channel.

I'm so glad you mentioned that movie in a thread that had very little to do with it, thank you!

What struck me the most is how she seems to be suspended in time - when the movie opened on the bright green and blue I wondered if I was watching something from the 70s, and her hairstyle and red lipstick make her look from a few decades before that. Except for the iPhones, everything else is stuck in time: the hospital, the cars, the vinyls records. It's like she's so untethered she's floating through time. I found that very unsettling, and it really reinforced the "is this all in her head" of it all. At the end, when she's wearing her white jacket, with her hair up, all of sudden she looks more of this earth and of this time, and it felt so strange to me, that it had all become so real and so grounded - their relationship, and her self.

I think I can't see mirror scenes without thinking of you, now. :)

Thanks for writing about this movie. I was mesmerized from the first shots by Natasa Stork's Gene Tierney coloration. And how she was shot from one side of her face and then the other as she spoke about her reason for coming to Budapest. I wasn't certain then that she was talking to someone else. Was she talking to herself, was her personality fragmented? That was my initial reaction. And as you mentioned, I was also struck by all the beautiful blues around her then and when she was waiting on the bridge.

Later, after her collapse and her decision not to fly back to the US, it felt like some gigantic "tell" that she was in her hotel room with those rich browns all around her. And then she looked in her notebook/calender and we see that Màrta's notes about meeting Jànos were in green - the color of the Liberty Bridge. I didn't notice that detail until I'd done a rewatch. The ugly apartment she chose was all beige/brown and green - in addition to having the view of the bridge. She wears a blue blouse and a green skirt when she comes to his book release. The first time Jànos waits for her, after she has stalked him to his home, Màrta sees him framed in green iron around the gate and against a beige and brown wall. They do their sidewalk dance against backgrounds of those colors. When he comes to her apartment for the first time, she isn't wearing anything blue. That didn't feel like giving up something of herself, more like being open. For me, the mixing of "her" blue, with the green of the Liberty Bridge, with the beige/brown that I associated with some sort of domesticity/satisfaction was a fascinating mixture, and a beautiful sort of integration. I had a harder time coming up with a consistent theme for the beige/brown. I didn't associate any colors with Alex, perhaps intentionally done to indicate his peripheral place in Màrta's mind? Maybe the flash of yellow when he drove her home for the first time - though I didn't associate that with him, more with her warning herself.

I liked that her friend Helen "saved" her by finding Jànos' overcoat and phone. Even with such a pared down life, a friend was valuable.

I also liked that the purchases associated with Jànos were too big to easily fit into her apartment. The couch only got through the door with some of the legs removed and the speakers required pulleys and had to come in through the window. Open up your life, Màrta!

I admired Màrta that she played with Jànos even though she was obsessed with him. She left the book release with Alex to tease him, she made him wait both with their hours-long walk on opposite sides of the street, and told him she had a dinner party. "Not so fast, mf-er, you made me doubt myself and now you've got some work to do."

I was surprised that the therapist used Rorschach test, I had thought they were considered unreliable. But in visiting the Wikipedia page on them, I see that this has been revised and they are thought to have some diagnostic value. Forensic psychologist use them and 80% of grad schools in psych use them. Learned something new. Also, from a photo of the guy, Dr. Rorschach was one good looking guy. Shame he died so young, probably from a burst appendix.

This was just an excellent film, so glad to have heard about it. And I was really drawn in by your great essay here.