With apologies to John Keats, who would totally not understand why his words were being used in this context, Hundreds of Beavers is “a thing of beauty and a joy forever”.

When something is sui generis, what more can you say? Point at the thing and tell others: “See that? It’s being itself. Fully.”

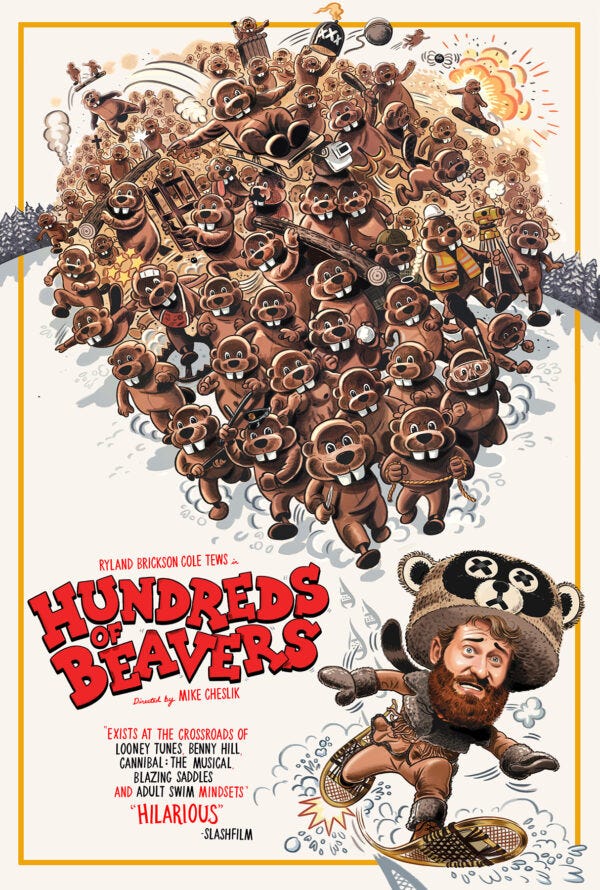

Hundreds of Beavers, the brainchild of Ryland Brickson Cole Tews and Mike Cheslik, is, first and foremost, itself. This is easier said than done. How many films AREN’T “themselves”, and instead are half-baked less-imaginative imitations of some other more successful thing? Hundreds of Beavers can be compared to other things but at a certain point the comparison falls apart. A list is more appropriate: Hundreds of Beavers is sort of like Benny Hill meets Laurel & Hardy meets Looney Tunes meets Jack London meets Monty Python meets It’s a Mad Mad Mad Mad World meets a furry convention (if the furries in question were all slapstick comedians). We should probably throw a little Scooby Doo in there too. As well as Mario Brothers and maybe even Pacman.

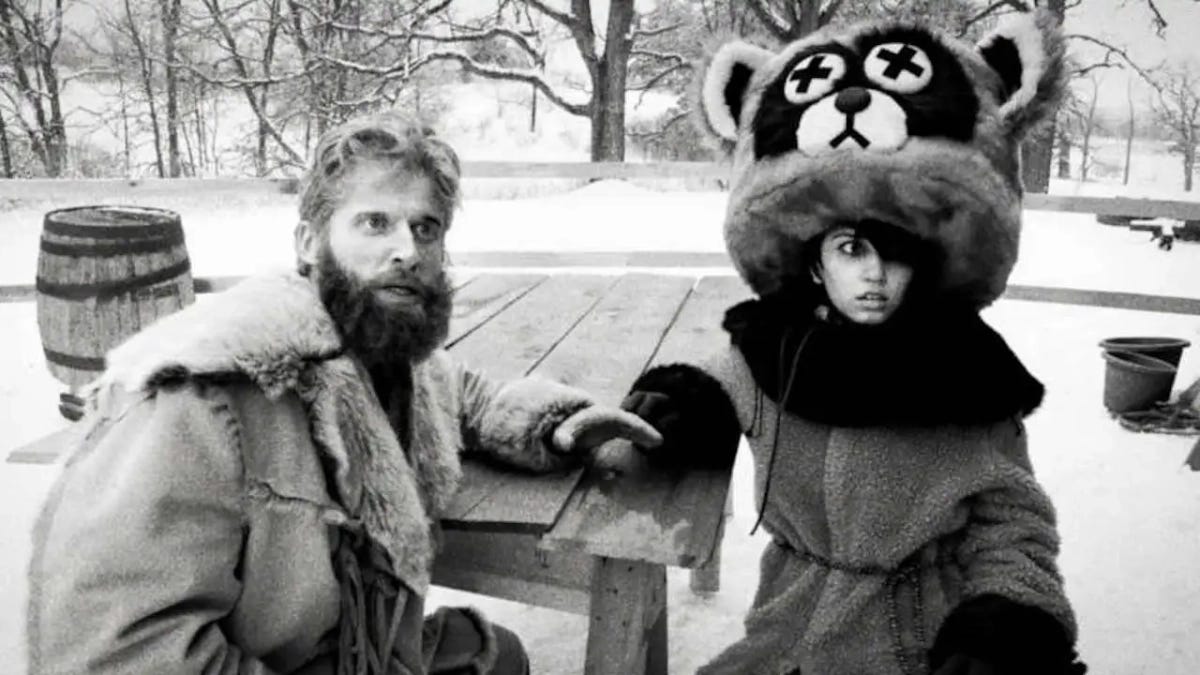

Filmed in splattery black-and-white, with no dialogue besides grunts, screams, and “…. huh??” sounds, peppered with visuals like intertitles and iris lens effects, Hundreds of Beavers is a throwback to silent film era comedies. There’s one moment stolen from a Mack Sennett Keystone Cops short as well as a “riff” on Buster Keaton’s famous falling-house stunt. These are homages, but without the overly respectful tone you often see in homages. Paying respect to a former time is different from inhabiting the former time to such a degree it doesn’t seem “former” at all. The “former” time required skill in pantomime, slapstick, timing … tricks of the trade used by performers in the teens and 20s of the 20th century, tools gained through years in vaudeville, and which were inheritances from commeda dell’arte, a legacy throughline. This is a lost tradition. People don’t “come up” that way anymore.

But the cast of Hundreds of Beavers seem as though they did come up this way. It’s a reminder that the old bits are the best bits because they have withstood the test of time. Some schtick comes out of a tradition 500, 600 years old. This shit worked across cultures and across millennia, in some cases. Slipping on a banana peel is a classic for a reason (it shows up here, as well, in a funny comment on the initial idea. Things go so poorly for our hero he can’t even do the ol’ slip-on-a-banana-peel correctly).

Mike Cheslik and Ryland Brickson Cole Tews, friends hailing from Whitefish Bay, Wisconsin, have been making movies together since high school. Their first venture, made for around $7,000, was Lake Michigan Monster, about a sea monster terrorizing the Great Lakes. It’s the platonic ideal of “let’s max out our credit cards and make a movie with our friends”. They had an idea to make a movie about fur trappers, and planned it out in a series of riff sessions, where every crazy idea - like “let’s have no dialogue and let’s do it with mascots” - stuck. The whole thing is powered by “why the fuck not?”

I wish more movies were bold enough to come from a place of “Why the fuck not?”

A pal on Facebook just posted about his annoyance with film critics who call a movie “messy”, “uneven” or “self-indulgent”, an annoyance I share. I’m annoyed because the language is lazy. It’s the language of a mediocre mindset. I left a comment along the lines of: some of the best art is messy and uneven and I want directors to “indulge” themselves. Please, please, indulge yourself. Let me see what you care about, what moves and obsesses you. John Cassavetes “indulged” himself. He had no interest outside the things that already interested him. (He said the only thing he cared about was love.) I love Cassavetes, but this goes for other directors as well, even if I don’t particularly care for their work. Who else is an artist supposed to indulge? A mediocre-minded audience who don’t like things “messy” or “uneven”?

Two childhood friends sitting in a bar saying, “let’s make a silent movie and let’s have hundreds of people in mascot costumes and let’s film it in the woods in the dead of winter” is way out on the fringes of the acceptable, and comes from extraordinary minds, not play-it-safe minds.

Hundreds of Beavers rattles along with a propulsive force, the various “bits” repeating over and over and over again, but intensifying with each repetition. The humor comes from you, the audience member, anticipating the disasters: “Oh God, he’s gonna fall through the ice again” or “Oh God, the log is going to fall the wrong way.” Anticipation of a known result is a bedrock of comedy. You the audience are superior to the idiot onscreen who believes, in delusional fashion, that THIS time, surely THIS time, his daring plan will work!

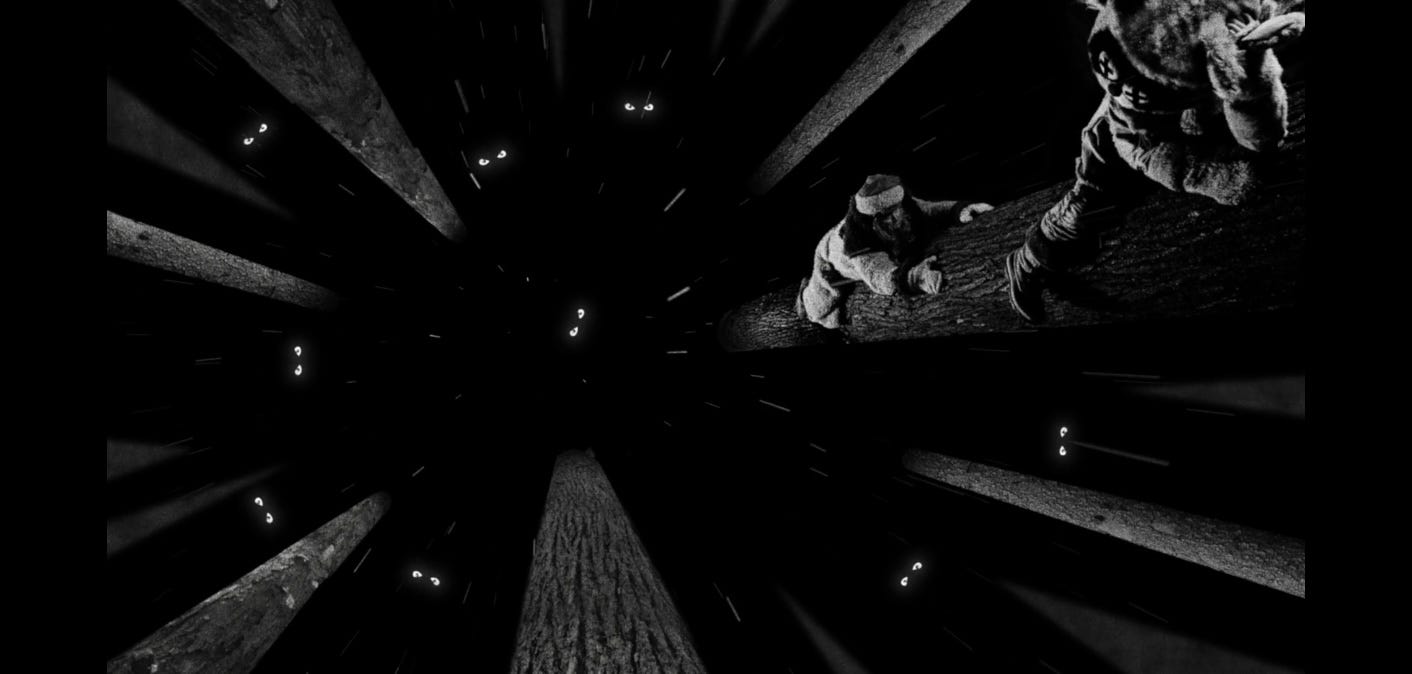

The cast is very small (if you don’t count the hundreds of beavers). Tews plays Jack Kayak, first seen in a musical number, developing an “applejack” cider, living high on the hog before quickly becoming an alcoholic, and ruining his fortunes. Abandoned in the snowy wilderness, he tries to become a fur trapper, but is stopped at every turn by Mother Nature’s brutality. He falls into holes under the snow. He can barely keep a fire going at night. He fails to catch a fish. For a while he pairs up with “The Master Fur Trapper”, a snow-encrusted beast of a man (Wes Tank) who shows him the ropes, but Jack Kayak is left on his own after a harrowing attack by a pack of wolves (first seen as glowing white cartoon eyes in the pitch black, snatching sled-dogs from the fireside, a scene straight out of Jack London’s White Fang).

Now Jack is really screwed. He chases bunnies holed up under the snow. He studies animal tracks in the snow. He experiments with different types of bait. He dodges falling icicles. He tries to fashion spears but he has nothing to cut them with. He finds his way to a trading post, run by an intimidating merchant (Doug Mancheski), who drives a hard bargain. The merchant’s daughter (Olivia Graves) is a giggly damsel peeking out at Jack from behind corners, crushing hard on him, and trying to hide it from her volatile dad. Jack gets one look at her and you can practically see his heart throbbing out of his chest, like Bugs Bunny’s.

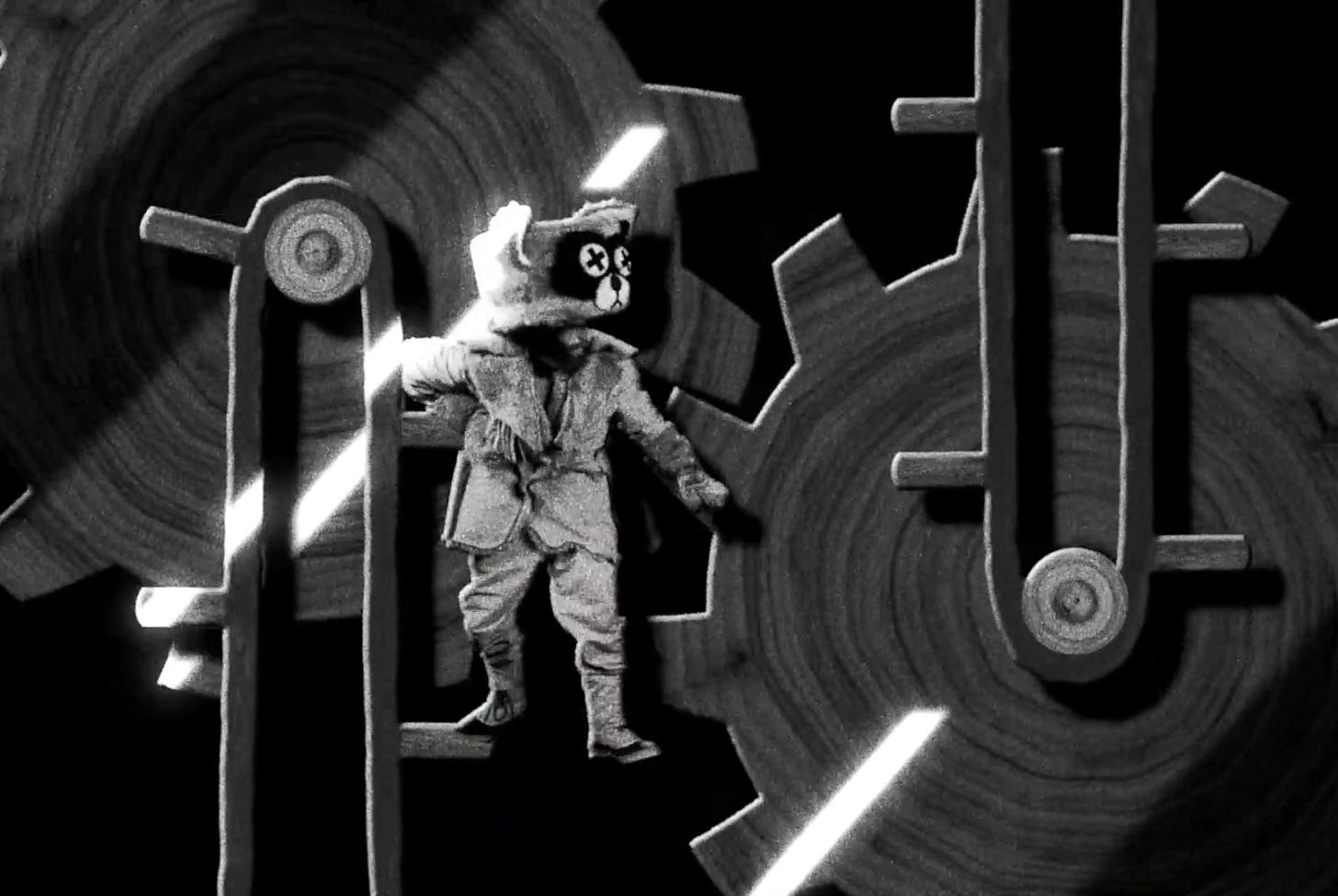

Jack lives surrounded by animals. These animals are all played by humans in animal costumes. When an animal dies, huge Xs appear in their eyes. (Jack’s square fur hat features X-ed out eyeballs). No attempt is made to make these animals seem like anything other than humans in costumes. There’s even a horse, like an old stage gag, with two humans underneath a blanket, as the front and back of the horse. (When someone tries to ride the horse, it does not go well.) Jack is clearly outnumbered and it takes all of his guile to survive. Even the bunnies defeat him.

The beavers are another issue entirely. They appear as a mindless almost fascistic crowd, moving as one, seen in the distance carrying huge logs across the icy white expanses. What are they building? Are they here to help or to harm? The bunnies are few and far between and easily handled. But Jack goes up against the beavers and is so outnumbered chaos ensues.

The beavers are building a dam, yes, as per their biological imperative. But the dam is as big as the Hoover, and its interior is a giant space filled with conveyor belts, pipes, interlocking wheels, and frightening drops into the abyss. Beavers stand in the bowels of the structure, wearing protective glasses, huddled over charts and plans. What are they up to? Jack is curious, but his befuddled clumsy approach shows his unpreparedness for the fight to come.

Nature is not benign in Hundreds of Beavers. The animals are not cute and/or cuddly. When they die, they become floppy stuffed animals with X’s in their eyes, and Jack hauls them off to the trading post, acquiring better weapons the more animals he brings. Meanwhile, the secret relationship between Jack and the merchant’s daughter progresses nicely, with the daughter, at one point, stripping down and doing a pole dance in the snow. Reader, I laughed out loud.

I was laughing at myself laughing. Every time Jack would let out a long agonized scream because he stepped on another giant thistle, or pierced his hand with a hook, or … or … I would start laughing, and not just because it was funny. I laughed because the repetition was satisfying. It’s Charlie Chaplin working on the assembly line. It’s I Love Lucy, where Lucy comes up with a cockamamie plan and you just know it’s all going to go to hell. I was in the hands of great schtick-makers, and I LOVE well-done schtick. I want more schtick in life. I surround myself with schtick-makers. If you don’t “get” schtick, you won’t last long in my crowd. I was a theatre kid. I majored in theatre. We were devoted to our jokes, and being as entertaining as possible for each other. (When critics betray annoyance at this kind of thing in movies, I think: “ah, so you weren’t a theatre kid obviously. It’s understandable why you would be embarrassed by goofballs doing jazz hands. You were probably the ones snickering at us in high school because we were so not cool.” In college, when we learned about commedia dell’arte, we pounced on the term “lazzi”. To this day, when someone lands on some funny bit, or acts out some eccentric human observation … we call these things “lazzis”. “Member that lazzi you did in the hotel lobby in West Hartford where you pretended to be an astronaut using the empty vase in the corner?” (True story.)

Hundreds of Beavers is one lazzi after another.

Cinematographer Quinn Hester deserves much credit in all of this. The visuals are stunning, and the challenges of filming out in the Wisconsin woods had to be considerable. It’s wild to watch because you know all those people in animal costumes are really out there in the snowy wilderness, carrying fake logs back and forth, and having fake fist fights in the snow drifts. (There are some clearly animated sequences, as well as an an animated woodpecker). But the sheer logistics of this thing dazzle the mind.

Tews is an astonishing physical comedian. I loved the freedom in what he was doing! This is lazzi heaven! There’s one scene where he gets trapped in a big wooden box rolling down a steep snowy hill. It’s all done in one shot, and Tews is clearly doing that stunt, in real time, falling out of the box at the bottom of the hill, dazed but unscathed. The sounds he makes are practically “ruh-roh!” in nature.

There’s obvious pleasure in coming up with different lazzis and finding ways to call back to them. I read one review which called this a little tiresome, the bits wore out their welcome. I strongly disagree. Wile E. Coyote has been entertaining audiences for almost 80 years at this point, and it’s the same bit over and over again.

By the time the chase sequence in Hundreds of Beavers arrives, where Jack is pursued by the vengeful army of beavers, all as an Oppenheimer-type beaver prepares to launch some kind of perhaps-sinister rocket - (maybe that’s what they’ve been building all along?) - we’re primed for it. The final sequence made me wish I had seen the film at a packed midnight screening. The chase is thrilling, catapulting on through disaster after disaster, the beavers multiplying, Jack finding himself in increasingly perilous positions, having to fight his way free.

It’s not every day you see a fascist army of beavers played by people wearing animal costumes, running through drifts in sub-zero weather.

Why the fuck not, I ask?

Pile lazzis upon lazzis. Make us laugh by giving us what we expect in a form we’ve never seen.

I’ve watched a lot of movies this year, many of which I’ve truly loved.

Hundreds of Beavers, though, did something different. It delighted me. An old-fashioned word for something so fresh and new you almost forget there are precedents. The precedents live in us already. Slipping on a banana peel is lodged in our DNA. We could probably use that space for more meaningful work to help society.

But the banana peel will not be dislodged to make room for other things. We can’t get rid of it. The banana peel makes demands: I know I’ve been used 189 times but use me again. I’m begging you. Trust me. I work every time.

We've been playing encores of this movie at the Grand Illusion, a local nonprofit movie theater that I volunteer at, for months. We have to keep adding shows because it keeps selling out (granted, it's only a 70ish-seat theater, but still). I projected one of the shows a while back, and the audience was ROARING. You could hear it from inside the booth (which, granted, is right behind the last row of seats, but still!).

My daughter and I loved this movie.

Every time he stepped on a thistle I grabbed my foot. It’s funny how something so “fake” can put you in the moment as much as any serious effect does. Gotta pin that on the actor.

The Wild Robot and C.S. Lewis lulled us into thinking beavers were trusty. But you have to keep an eye on those shifty rodents.